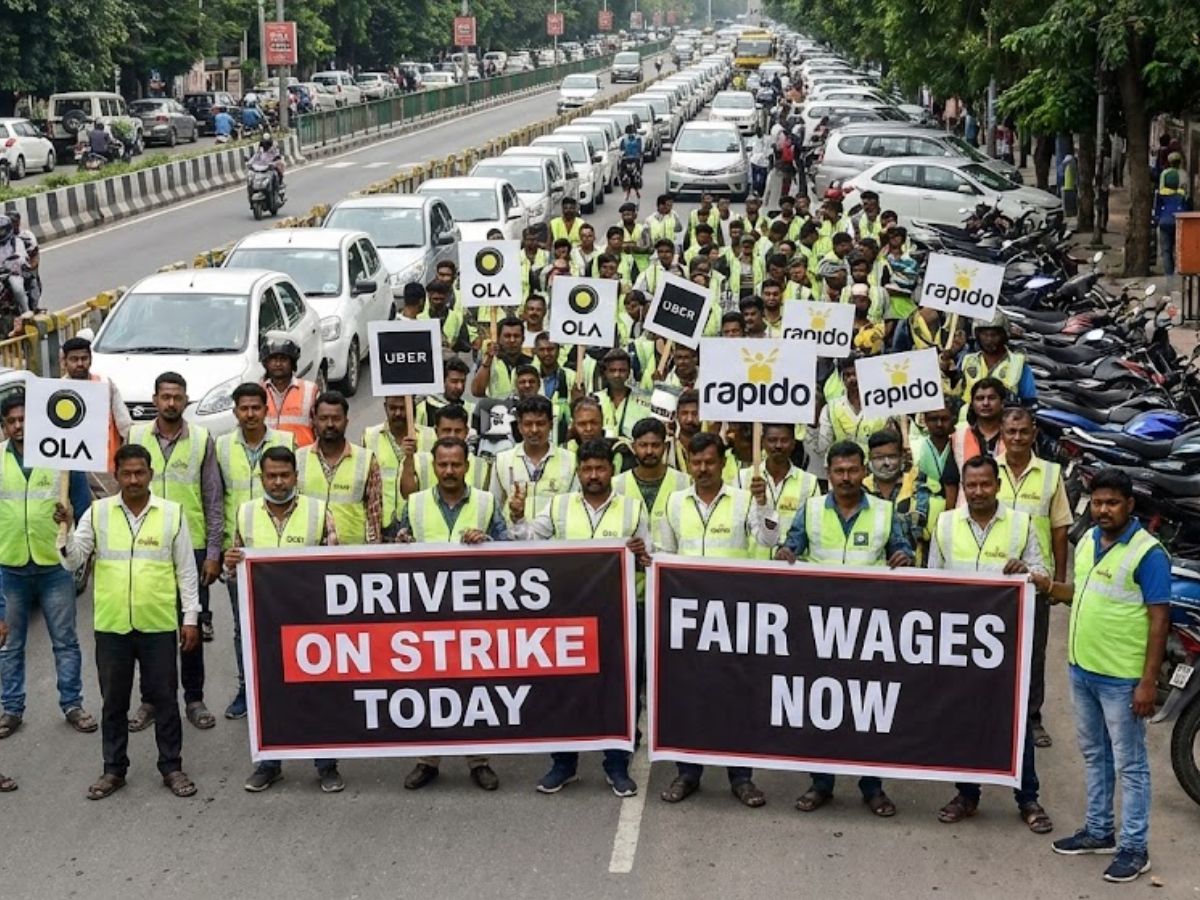

Commuters across India faced uncertainty and travel disruptions on Saturday, February 7, as drivers associated with major ride-hailing platforms—including Ola, Uber and Rapido—went on a coordinated nationwide strike. Dubbed the “All India Breakdown,” the protest saw thousands of app-based drivers simultaneously logging out of their platforms for up to six hours, impacting cab services, auto-rickshaws and bike taxis across several major cities.

The strike brought fresh attention to long-standing grievances within India’s rapidly expanding gig economy, particularly around fare regulation, income instability, and the lack of effective enforcement of existing rules governing digital transport aggregators. While services began resuming later in the day as drivers gradually logged back in, the protest underscored growing unrest among app-based transport workers and raised questions about how long the current regulatory vacuum can persist.

What Is the ‘All India Breakdown’ Strike?

The February 7 protest was conceived as a nationwide, synchronised shutdown of app-based transport services, with drivers collectively switching off their ride-hailing apps during peak morning hours. According to unions, the strike was scheduled to run from 6 am to noon, although participation varied by city and platform.

The action affected cab services, auto-rickshaws and bike taxis, leaving commuters in many cities scrambling for alternatives. Metro rail services, state-run buses, street-hailed autos and private taxis became the primary fallback options for passengers, especially in large metropolitan areas.

Unions organising the strike described it as a warning shot aimed at both the government and ride-hailing companies, signalling that unresolved policy gaps and declining driver incomes could no longer be ignored.

Who Called the Strike?

The strike was spearheaded by the Telangana Gig and Platform Workers Union (TGPWU), with backing from multiple labour organisations across the country. Among them was the Maharashtra Kamgar Sabha, which represents app-based drivers in the state and has been vocal about compliance costs and regulatory inconsistencies.

Announcing the protest on social media platform X, TGPWU stated:

“App-based transport workers across India will observe an All India Breakdown on 7 Feb 26. No minimum fares. No regulation. Endless exploitation.”

The union framed the strike as a response to what it sees as systemic exploitation within platform-based transport work, accusing aggregator companies of profiteering while drivers struggle to earn sustainable incomes.

Hon’ble @nitin_gadkari ji, @MORTHIndia @Ponnam_INC App-based drivers and riders across India demand government-notified minimum base fares for #Ola, #Uber, #Rapido #Porter other aggregators, as mandated under Motor Vehicle Aggregator Guidelines, 2025. pic.twitter.com/epMHtJKOXS— Telangana Gig and Platform Workers Union (@TGPWU) February 1, 2026

The Core Issue: Fare Fixation Without Regulation

At the heart of the protest lies a single, recurring grievance: the absence of government-notified minimum base fares for app-based transport services.

Despite the notification of the Motor Vehicle Aggregator Guidelines, 2025, unions allege that ride-hailing platforms continue to fix fares unilaterally. According to drivers, this has resulted in unpredictable earnings, downward pressure on incomes, and excessive dependence on opaque algorithm-driven pricing systems.

In one of its statements, the Telangana-based union said:

“Despite Motor Vehicle Aggregator Guidelines, 2025, platforms continue to fix fares arbitrarily. Our demands are clear: Notify minimum base fares, end misuse of private vehicles for commercial rides.”

Unions argue that without a legally enforced base fare, companies can reduce prices at will to gain market share, leaving drivers to absorb the financial shock.

Two Key Demands Driving the Nationwide Protest

While multiple issues were flagged by different unions, organisers of the strike placed two primary demands before the central and state governments.

-

Notification of Minimum Base Fares

The foremost demand is for the immediate notification of minimum base fares for all forms of app-based transport, including: Cabs, Auto-rickshaws, Bike taxis and other aggregator-driven passenger services.

According to unions, these fares must be finalised in consultation with recognised driver and worker unions and aligned with the provisions of the Motor Vehicle Aggregator Guidelines, 2025.

TGPWU general secretary Shaik Muhammad Khan told ThePrint:

“Companies can charge any price they want because base fares are not notified.”

Without a mandated floor price, drivers say they are forced to accept trips that barely cover fuel, maintenance and platform commissions, let alone provide a dignified livelihood.

-

Ban on Private Vehicles Used for Commercial Rides

The second major demand is a strict ban on the use of private, non-commercial vehicles for commercial transport of passengers or goods.

Unions argue that allowing private vehicles to operate commercially creates unfair competition for licensed drivers who comply with permit, insurance and regulatory requirements. This practice, they say, worsens income pressure for drivers who have invested heavily in commercial licences and vehicle compliance.

App-based transport workers across India will observe an All India Breakdown on 7 Feb 26.

No minimum fares. No regulation. Endless exploitation.

Govt must act NOW.

Millions of app-based drivers are pushed into poverty while aggregators profit.

Govt silence = platform impunity pic.twitter.com/zT3e6eZWjm— Telangana Gig and Platform Workers Union (@TGPWU) February 4, 2026

Additional Grievances Raised by Driver Unions

Beyond the two headline demands, driver organisations across states highlighted several related concerns contributing to the protest.

-

Panic Button Devices and Rising Compliance Costs

In Maharashtra, the Maharashtra Kamgar Sabha pointed to the cost of mandatory panic button installations as a major flashpoint.

According to the union, while the central government has approved 140 panic button device providers, the Maharashtra government has declared nearly 70% of them unauthorised. This has forced drivers to uninstall existing devices and spend around ₹12,000 again on new installations.

Unions say this has imposed an avoidable and recurring financial burden on drivers already grappling with low and uncertain incomes.

-

Unlicensed and Illegal Bike Taxi Operations

Driver bodies have also raised alarms about the proliferation of unlicensed bike taxi services operating in regulatory grey zones.

According to unions, illegal bike taxis not only undercut licensed drivers but also expose both riders and drivers to serious risks. In cases of accidents involving such vehicles, unions allege that victims are often denied insurance coverage, leaving them financially vulnerable.

A Letter to the Centre and Unresolved Policy Gaps

As part of the strike mobilisation, unions addressed a letter to Union Minister for Road Transport and Highways, Nitin Gadkari, drawing attention to what they described as “long-pending and unresolved issues” faced by app-based transport workers nationwide.

The letter emphasised that in the absence of government-fixed fare systems, platforms like Ola, Uber, Rapido and Porter continue to set prices independently.

In a statement, the union said:

“In the absence of government-regulated fare structures, aggregator companies continue to unilaterally fix fares. This has led to severe income insecurity, exploitation, and unsustainable working conditions for millions of transport workers.”

App-based transport workers across India will observe an All India Breakdown on 7 Feb 26.

No minimum fares. No regulation. Endless exploitation.

Govt must act NOW.

Millions of app-based drivers are pushed into poverty while aggregators profit.

Govt silence = platform impunity pic.twitter.com/zT3e6eZWjm— Telangana Gig and Platform Workers Union (@TGPWU) February 4, 2026

Impact on Commuters Across Major Cities

The immediate impact of the strike was felt most acutely in large metropolitan areas.

Early Saturday morning, commuters in Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru and Hyderabad reported difficulty booking rides through popular ride-hailing apps. Many users found no drivers available on Ola and Uber, while others encountered repeated cancellations.

With app-based services largely unavailable, passengers were forced to:

-

Switch to metro rail services

-

Rely on state transport buses

-

Hire street autos and private taxis

In some cases, commuters faced higher out-of-pocket expenses or longer travel times due to limited alternatives.

Mixed Participation and Gradual Resumption of Services

While thousands of drivers participated in the shutdown, union leaders acknowledged that participation levels varied by city and platform.

In cities like Mumbai, rides became available intermittently as drivers logged off and back on throughout the day. Although the strike was scheduled for six hours, it remained unclear how many drivers would observe it in full.

Local unions reported participation from drivers in Bengaluru, Chennai, Hyderabad, Kochi, Kolkata, Pune and Nagpur, among other cities.

By later in the day, many drivers had begun logging back into their apps, and services gradually resumed, though some commuters continued to report sporadic disruptions.

Official Silence and Political Response

As of Saturday, Ola and Uber had not responded to requests for comment on the strike or the drivers’ demands.

Government response was also limited, though developments in Maharashtra suggested potential engagement. The Traffic Rental and Taxi Association of Maharashtra issued a statement saying it would write to Chief Minister Eknath Shinde regarding fare policy-related issues.

The association also said that the Chief Minister would be holding a meeting with stakeholders and driver unions later in the day, raising hopes of dialogue—at least at the state level.

Part of a Broader Wave of Gig Worker Protests

The February 7 strike is not an isolated event but part of a wider wave of mobilisation among gig and platform workers.

In December 2025, food delivery and quick-commerce workers staged protests over low payouts and demanding better working conditions, including during peak business periods.

These actions reflect growing discontent across platform-based industries, where workers argue that algorithm-driven systems prioritise growth and profitability over fair compensation.

Economic Survey Flags Gig Worker Vulnerabilities

Concerns around gig employment have also been flagged at the policy level. The Economic Survey 2025–26, released on January 30, highlighted income instability as a major issue even as the gig economy continues to expand rapidly.

According to the Survey:

-

India had around 1.2 crore gig workers in FY25, up from 77 lakh in FY21

-

Gig work now accounts for over 2% of the workforce

-

The sector is growing faster than overall employment

However, the Survey also noted that around 40% of gig workers earn less than ₹15,000 a month, underscoring the precarious nature of platform-based livelihoods.

It called for greater transparency in algorithm-driven systems used by digital platforms, echoing concerns raised by unions about opaque pricing and incentive mechanisms.

What Lies Ahead?

While the February 7 strike was limited in duration, its implications may be longer-lasting. With gig workers demonstrating their ability to mobilise nationwide, pressure is mounting on governments to move beyond guidelines and translate policy intent into enforceable regulation.

For commuters, the strike served as a reminder of the human labour underpinning app-based convenience. For policymakers, it may signal the first domino in a broader push toward fare regulation and worker protection in India’s gig economy.

As drivers return to the roads and apps resume normal operations, the larger question remains unanswered: will the government act before the next shutdown, or will the ‘All India Breakdown’ become a recurring feature of India’s urban transport landscape?

With inputs from agencies

Image Source: Multiple agencies

© Copyright 2025. All Rights Reserved. Powered by Vygr Media.