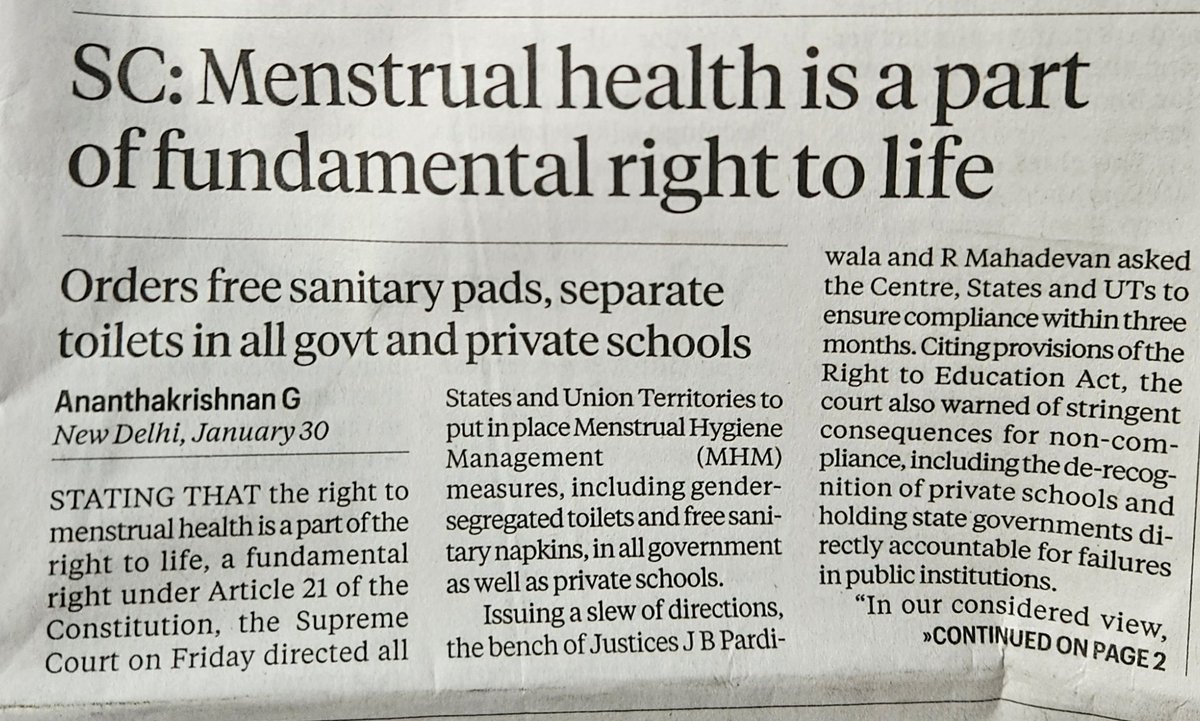

On January 30, the Supreme Court of India did something that decades of welfare schemes, awareness campaigns, and civil society advocacy could not fully achieve: it moved menstruation out of the shadows of policy discretion and into the firm terrain of constitutional rights. By declaring menstrual health and hygiene a fundamental right under Article 21 of the Constitution, the Court reframed an issue long dismissed as a “women’s matter” or a welfare concern into a question of dignity, bodily autonomy, equality, and state accountability.

For activists, public health experts, educators, and organisations working on menstrual health, the verdict marks a long-awaited moment of recognition. “Until now, the country did not acknowledge menstrual health as a fundamental right, so all of us who work in this space would have to keep proving the importance of the work we do,” says Dilip Pattubala, founder of Bengaluru-based non-profit Uninhibited. The judgment, he notes, finally legitimises decades of effort.

Yet even as the ruling is widely celebrated, experts across disciplines caution that constitutional recognition is only the beginning. The real test lies not in what the judgment promises, but in how it is implemented—and whether it can dismantle the stigma, silence, and structural barriers that surround menstruation in India.

What the Supreme Court Ordered—and Why It Matters

The bench comprising Justices JB Pardiwala and R. Mahadevan issued a series of binding directions to states, Union Territories, and both government and private schools. These include the mandatory provision of free sanitary pads to girls, the availability of gender-segregated toilets with clean water, and safe disposal mechanisms in all schools. Schools are also required to set up “Menstrual Health Management Corners” stocked with spare uniforms, innerwear, disposable bags, and essential hygiene supplies.

Importantly, the Court warned that failure to implement the Centre’s Menstrual Hygiene Policy for School Going Girls would invite punitive action. Financial constraints, it clarified, cannot be cited as an excuse for non-compliance. Private schools that fail to adhere to the directions risk de-recognition.

The Court also mandated special provisions for girls with disabilities, including wheelchair-accessible toilets and assistive facilities—an often overlooked dimension of menstrual equity.

By locating menstrual health within Article 21, which guarantees the right to life and personal liberty, the Court reaffirmed its long-standing interpretation that “life” does not mean mere survival, but living with dignity, health, and self-respect. It also drew strength from Article 15(3), which empowers the State to make special provisions for women, reinforcing the principle of substantive equality.

From Welfare to Rights: A Constitutional Shift

For decades, menstrual hygiene in India has existed in a policy grey zone—addressed through schemes, pilot projects, and CSR initiatives, but rarely enforced as a legal obligation. Advocate Tahini Bhushan describes the verdict as “a start of sorts,” noting that until now, menstrual hygiene policies were largely voluntary or locally driven.

“This verdict will impact how policies are now going to be implemented,” she explains. “You can expect amendments in laws, especially by-laws, with respect to schools and educational institutions.”

The shift from welfare to rights is significant because it transforms the relationship between citizens and the State. As Arundati Muralidharan, public health professional and co-founder of Menstrual Health Action for Impact (MHAi), points out, the difference now is accountability. “We can hold the State responsible,” she says.

The Court went further, explicitly recognising “menstrual poverty”—the inability to access affordable menstrual products and facilities—as a violation of bodily autonomy and dignity. It held governments accountable for lapses in government-run schools and empowered authorities to act against errant private institutions.

Bringing Menstruation into the Public Sphere

Beyond infrastructure and products, the judgment carries deep symbolic and cultural weight. By declaring that menstruation should not be a source of shame or stigma, the Court challenged one of the most entrenched taboos in Indian society.

Mumbai-based psychotherapist Ahla Matra sees the ruling as a crucial psychological intervention. “It takes menstruation from a private ‘women’s issue’ to one of fundamental rights and dignity,” she says. While acknowledging that legal change alone cannot erase centuries of stigma, she believes it “definitely cracks a wall.”

The Court explicitly called for sensitisation of men and boys, emphasising that male teachers have a “multifaceted role” to play by integrating accurate, stigma-free information into lessons. This is a notable departure from the traditional approach that treats menstruation as something to be managed quietly by girls alone.

As Matra explains, shame thrives in silence. “Psychologically, shame thrives when there is no discussion or discourse around one’s experience. The hope is that this judgment will bring menstruation from private life to the public sphere—and reframe it as a public responsibility at schools, workplaces, and other institutions.”

The Messages Young Menstruators Absorb

Experts warn that the stigma surrounding menstruation is neither natural nor accidental. It is manufactured at the intersection of patriarchy, religion, caste hierarchies, and capitalism.

“When menstruation is seen as a marker of ‘maturity,’ society responds with surveillance, control, and moral policing of menstruators’ bodies,” Matra explains. The result is an overemphasis on how women’s bodies should exist in public and private spaces, reinforced by caste-based notions of purity and pollution that exile menstruating people—physically and socially—during their periods.

These ideas seep into everyday instructions given to young menstruators: dispose of pads discreetly, buy them quietly, make sure you don’t stain your clothes. “That’s really sending a message to the mind of a young menstruator,” Matra says.

Capitalism, she adds, has exploited this shame by aggressively marketing concealment products—leak-proof, smell-proof, invisible—reinforcing the idea that menstruation must be hidden at all costs. The Supreme Court’s recognition of menstrual hygiene as a rights issue, she hopes, can begin to delegitimise these traditions of control and reframe them as violations of rights.

Pattubala echoes this concern, noting that stigma among decision-makers themselves can undermine policy implementation. “If they are not comfortable talking about it with one another, that discomfort dictates how the policy will be implemented on the ground,” he says.

He points to a telling example: despite being included in NCERT textbooks, chapters on reproduction are routinely skipped by government school teachers. Even examination committees avoid setting questions on the topic, knowing it is not being taught.

The Distribution Dilemma: Pads Are Not the Whole Answer

While the Court’s focus on free sanitary pad distribution is widely welcomed, experts caution against treating pads as the sole or “holy grail” solution.

India’s menstrual product ecosystem has evolved significantly over the past two decades. As Lakshmi Murthy, president of Rajasthan-based Jana Sansthan, notes, there are now multiple options beyond disposable pads. Menstrual cups, reusable cloth pads, and menstrual underwear offer alternatives that may be more suitable for some users.

However, the judgment’s emphasis on oxo-biodegradable sanitary pads has raised concerns. Muralidharan argues that the Court could have referred to the Bureau of Indian Standards, which has developed norms for a range of menstrual products, including menstrual underwear.

Pattubala shares that Uninhibited saw greater success distributing menstrual cups in Karnataka and plans to scale up with state government support. “There are alternate products available, so we should give them a choice to choose what suits them,” he says.

Environmental concerns further complicate the picture. Experts warn that oxo-biodegradable pads are not truly biodegradable. In areas without organised waste collection, they often end up in landfills. Rural disposal systems, Murthy explains, are vastly different from those in cities. Incinerators require reliable electricity, and smaller units often produce acrid smells, creating new challenges.

Absenteeism, Dropouts, and the Myth of a Single Cause

In pronouncing the verdict, the Supreme Court quoted American social activist Melissa Burton: “A period should end a sentence—not a girl’s education.” The bench linked the lack of sanitary products and disposal mechanisms to absenteeism and school dropouts among girls.

While experts agree that access to products and toilets is crucial, they caution against oversimplifying the problem. “Absenteeism and dropouts are complex issues,” says Muralidharan.

Period pain, excessive bleeding, fatigue, stigma, and discrimination all contribute. In many cases, when a girl attains menarche and enters adolescence, parents withdraw her from school to marry her off. Menstrual challenges thus intersect with early marriage, gender norms, and poverty.

Addressing logistics without tackling shame and stigma, experts argue, will only yield partial results.

Menstrual Health Through a Rights Lens

The Supreme Court’s decision in Dr. Jaya Thakur v. Government of India & Ors. marks a significant expansion of Article 21 jurisprudence. By recognising menstrual health as integral to the right to life, the Court bridged the gap between constitutional ideals and lived realities.

Government data shows progress in building separate toilets for girls, but usability remains a problem. Locked facilities, lack of water, poor maintenance, and absence of disposal mechanisms render infrastructure ineffective. Surveys consistently show that many adolescent girls avoid school during menstruation—not just because of physical discomfort, but due to anxiety, embarrassment, and institutional neglect.

With an estimated 36 crore women of menstruating age in India, and adolescent girls aged 10–19 forming at least a third of all menstruators, the scale of the issue is immense. Many young women discontinue education due to inadequate facilities, leading to early marriage and motherhood, particularly in rural areas.

By making menstrual hygiene judicially enforceable, the Court aligned India with international human rights standards, including UN Human Rights Council resolutions calling for universal access to safe, affordable menstrual hygiene products and facilities.

A Beginning, Not the Destination

The judgment’s success will ultimately depend on execution—on public campaigns, teacher sensitisation, curriculum integration, parental engagement, and sustained monitoring. Constitutional recognition alone cannot transform classrooms or dismantle centuries-old taboos.

Still, the message is unambiguous: access to menstrual hygiene is not charity, convenience, or choice. It is a condition of dignity, equality, and meaningful education.

If India’s development narrative is to be credible—if slogans of inclusion and progress are to mean anything—women’s health and rights must be placed at the centre. Freedom from menstrual stigma is not just about physical comfort. It is about mental, social, and constitutional liberty.

The Supreme Court has drawn the line. Now, it is up to the State—and society—to decide whether it will truly cross it.

With inputs from agencies

Image Source: Multiple agencies

© Copyright 2025. All Rights Reserved. Powered by Vygr Media.