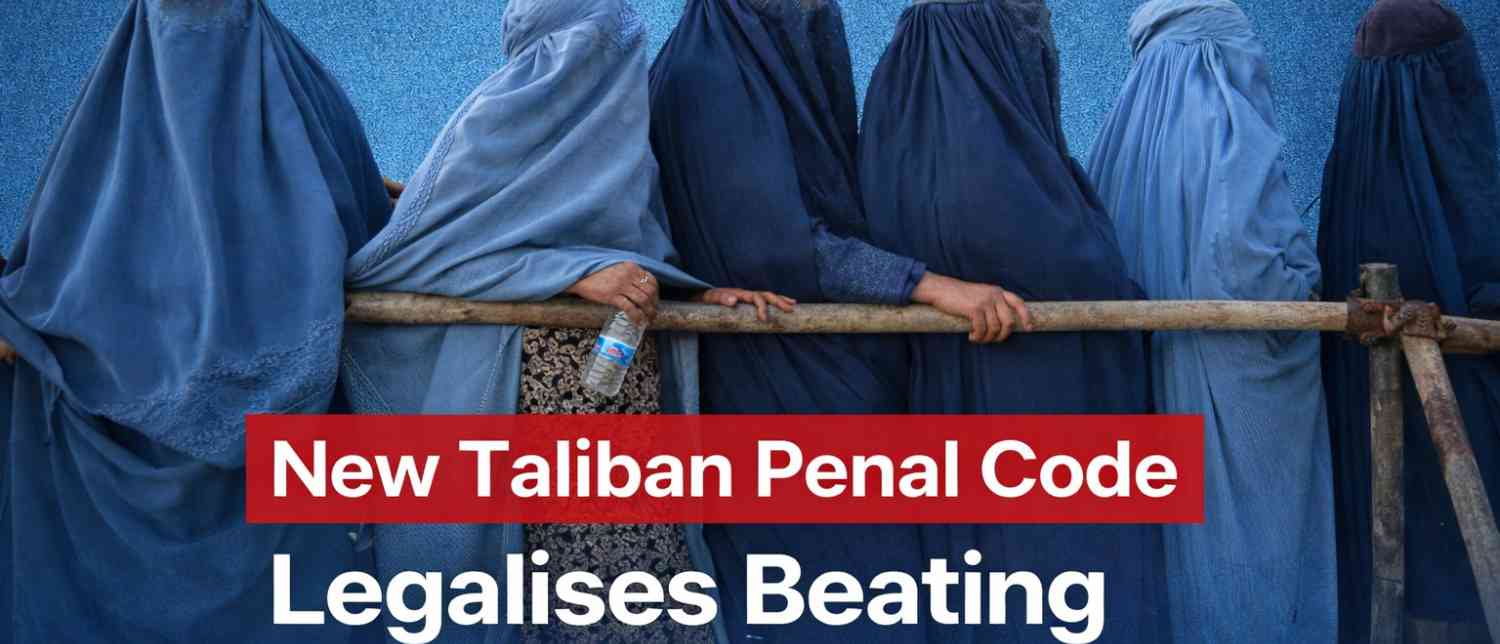

“Break the spine, but spare the bones.” That chilling phrase captures the spirit of the Taliban’s newly formalised penal code in Afghanistan—a 90-page legal framework that critics say institutionalises domestic violence, entrenches caste-like hierarchies, and accelerates the systematic erasure of women from public life.

Signed by the Taliban’s supreme leader, Hibatullah Akhundzada, the new criminal code permits husbands to physically discipline their wives and children, provided the punishment does not result in “broken bones or open wounds.” Human rights organisations warn that this effectively legalises domestic violence under state authority.

But this development is not an isolated policy shift. It is the culmination of a sweeping rollback of women’s rights across Afghanistan since the Taliban’s return to power—impacting education, employment, healthcare, mobility, justice, and political participation.

Legalising Domestic Violence: What the Penal Code Says

At the heart of the controversy is the Taliban’s 90-page penal code, reportedly titled De Mahakumu Jazaai Osulnama, which has been circulated to courts nationwide.

Under the new framework:

-

Husbands may physically punish their wives and children as long as no fractures or “open wounds” are inflicted.

-

If a husband uses what the code describes as “obscene force” resulting in visible bruises or fractures, the maximum penalty is 15 days in prison.

-

Conviction requires the wife to prove the abuse in court under strict procedural constraints.

-

The woman must present her injuries to a judge while remaining fully covered.

-

She must also be accompanied by her husband or a male chaperone (mahram)—even if the husband is the accused.

Human rights experts confirm that the code does not explicitly prohibit or condemn physical, psychological, or sexual violence against women.

The code also abolishes the 2009 Elimination of Violence Against Women (EVAW) law, introduced under the previous US- and NATO-backed government. That law had criminalised forced marriage, rape, and various forms of gender-based violence, prescribing penalties ranging from three months to a year for domestic violence.

Its removal marks a dramatic regression in legal protections.

A Caste-Based Justice System

Beyond gender discrimination, the penal code introduces a rigid social hierarchy that determines punishment not by the severity of the crime, but by the social status of the accused.

Article 9 divides Afghan society into four categories:

-

Religious scholars (ulama)

-

The elite (ashraf)

-

The middle class

-

The lower class

Punishments vary dramatically:

-

If a religious scholar commits a crime, the response is limited to advice.

-

If an elite member offends, they may receive advice and possibly a court summons.

-

Middle-class offenders face imprisonment.

-

Lower-class individuals may face both imprisonment and corporal punishment.

The code also distinguishes between individuals considered “free” and those treated as “slaves.” Women, according to rights groups, are effectively placed on the same level as “slaves,” with provisions allowing husbands—or so-called “slave masters”—to administer discretionary punishment, including beatings.

Serious offences are to be punished by Islamic clerics rather than correctional services. For lesser offences, the code prescribes ta’zir (discretionary punishment), which in the context of a wife as the “offender”, may mean a beating administered by her husband.

Observers note that while some interpretations draw on historical readings of Islamic jurisprudence, the explicit codification of such a hierarchy marks a sharp departure from recent Afghan legal standards.

Criminalising Women Seeking Safety

One of the most alarming provisions concerns women who attempt to leave abusive environments.

According to Rawadari, an Afghan human rights organisation operating in exile, Article 34 states that:

-

If a woman repeatedly goes to her father’s or relatives’ home without her husband’s permission and refuses to return,

-

She—and any family member who shelters her—can face up to three months’ imprisonment.

In effect, a woman fleeing abuse may be criminalised simply for seeking refuge.

Married women can also reportedly be jailed for up to three months for visiting relatives without their husband’s permission, even if escaping violence.

Justice in Name Only

Although the penal code technically allows women to file complaints, the barriers are overwhelming.

A legal adviser in Kabul described the process as “extremely lengthy and difficult.” She cited a case in which a woman assaulted by a Taliban guard while visiting her imprisoned husband was unable to file a complaint because authorities required her husband—who was in prison—to serve as her male chaperone in court.

Women must:

-

Appear fully covered before male judges.

-

Be accompanied by a mahram.

-

Present evidence of serious bodily harm.

Police and judges reportedly dismiss domestic violence complaints as “private matters.”

Copies of the new code have been distributed to courts across Afghanistan, and a separate directive allegedly criminalises public discussion of the code itself. Rights groups say people are afraid to speak out—even anonymously.

Education: A Generation Locked Out

The penal code exists within a broader framework of restrictions that have devastated women’s lives.

Girls are barred from attending secondary school beyond grade six. Women are prohibited from enrolling in universities or sitting for entrance examinations.

Entire fields of study—including engineering, agriculture, journalism, mining, and veterinary sciences—have been closed to women.

Many girls’ education centres have been shut down. In some provinces, local orders reportedly ban girls aged 10 and above from attending even lower grades.

Additional measures include:

-

Strict dress codes, including full-face coverings as a condition for attendance.

-

Curriculum changes reducing secular subjects and expanding religious instruction.

The result is the systematic narrowing of educational and professional futures for Afghan women.

Employment Bans Across Sectors

Women have been barred from:

-

Most government jobs

-

Many private-sector roles

-

Working with national and international NGOs

-

Employment with the United Nations

Previously, NGOs and UN agencies were significant sources of employment and essential services for women.

Women-run businesses—such as bakeries and small shops—have been shut down. Women are barred from public-facing roles like flight attendants.

At the same time, institutions supporting survivors of gender-based violence have been dissolved, stripping women of workplace and domestic protections.

Mahram Rules and Restricted Movement

Under Taliban rule, women must be accompanied by a close male relative (mahram) for most travel beyond short distances, including:

-

Trips to health facilities

-

Workplaces

-

Government offices

Women are restricted from using public transport independently. Cafés and public venues are barred from serving unaccompanied women.

In some areas, hospitals reportedly refuse to treat female patients unless accompanied by a male guardian—effectively denying independent access to healthcare.

Women are also banned from parks, gyms, public baths, and community spaces, shrinking their presence in public life.

Mandatory Dress Codes and Collective Punishment

Strict hijab regulations require adherence to detailed guidelines, with some institutions mandating full-body coverings such as the chadari or burqa.

Non-compliance carries consequences beyond the individual woman:

-

Women risk losing government jobs.

-

Male relatives may face suspension from their posts if deemed responsible for allowing non-compliance.

Women are instructed not to visit male tailors and to limit social interactions outside the home.

Harsh Punishments for “Moral Crimes”

Public flogging—up to 39 lashes or more—and prison terms ranging from one to seven years have been imposed for so-called “moral crimes,” including adultery or “illegitimate relations.” Women are disproportionately affected.

Taliban leaders have threatened the resumption of public stoning for adultery, though such executions have not been widely reported.

Erasing Women from Public Life

Women have been excluded from:

-

Senior political positions

-

Judicial posts

-

Security roles

Mechanisms for women’s participation in governance have been dismantled.

Women’s rights activists and protesters have faced:

-

Violent dispersal

-

Arrest

-

Enforced disappearances

-

Alleged torture in detention

Women journalists endure strict censorship, harassment, and on-air face-covering requirements, forcing many to leave the profession.

International Condemnation

Human rights organisations and UN experts have described the Taliban’s legal framework as an unprecedented rollback of women’s rights.

Rawadari has called on the United Nations and international bodies to immediately halt the implementation of the criminal procedure code and use all legal instruments to prevent it from becoming entrenched.

Reem Alsalem, the UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women and girls, wrote on X that the implications of the code for women and girls are “simply terrifying,” questioning whether the international community would act.

Public figures have also condemned the move. Indian actor Swara Bhasker called the Taliban “absolute monsters,” describing the law as “an insult to humanity and to the religion they claim to represent.” Actor Gauahar Khan labelled the development “disgusting,” while Nandish Sandhu questioned its rationale.

A Systematic Dismantling of Rights

From banning education and employment to codifying domestic violence and enforcing caste-based punishments, the Taliban’s legal regime represents a comprehensive restructuring of Afghan society.

Women now face shrinking access to:

-

Education

-

Work

-

Healthcare

-

Justice

-

Public participation

Human rights advocates argue that the policies amount to systematic gender-based discrimination and may meet the threshold for crimes against humanity.

As the restrictions deepen, Afghan women and girls are not merely being marginalised—they are being methodically erased from public life, one decree at a time.

With inputs from agencies

Image Source: Multiple agencies

© Copyright 2025. All Rights Reserved. Powered by Vygr Media.