While inflation and affordability dominate conversations in the United States, a very different anxiety grips China. Instead of rising prices, many Chinese consumers are increasingly troubled by deflation, economic slowdown, and a growing sense of uncertainty about the future. These economic concerns, however, are only one layer of a deeper emotional and social malaise—one that is manifesting in unexpected cultural symbols, viral technology, and shifting lifestyles across the country.

From a frowning plush horse that has captured the public imagination to a controversial app designed to alert loved ones if someone dies alone, China’s current moment is revealing profound changes in how people live, work, and cope with loneliness in an era of slowing growth.

A Plush Toy That Speaks Volumes About Public Mood

To understand contemporary Chinese consumer sentiment, one does not need to pore over macroeconomic charts. Sometimes, the most revealing indicators sit quietly on a toy-store shelf.

In Beijing, toy seller Gao Lan has been struggling to keep one particular item in stock ahead of the Year of the Horse: a plush horse with a distinctly sorrowful expression. Known across social media as the “crying horse,” the toy’s downturned mouth was not a deliberate design choice. According to state media, a factory worker accidentally sewed the horse’s smile upside down. Instead of rejecting the flawed batch, consumers embraced it.

The plushie rapidly became a runaway hit.

“Nowadays, there is so much stress in our society,” Gao explained. “The crying horse reflects how people feel inside.”

For many buyers, the toy is less a children’s product and more an emotional outlet. Xiao Juan, one such customer, put it bluntly: “There is a lot of bitterness and a feeling of unfairness. If you can’t cry out loud, this horse can cry for you.”

The horse’s popularity reflects a broader sense of gloom taking hold in Chinese society—a feeling that economic momentum has stalled and personal prospects feel increasingly fragile.

The Viral App That Asked the Unthinkable Question

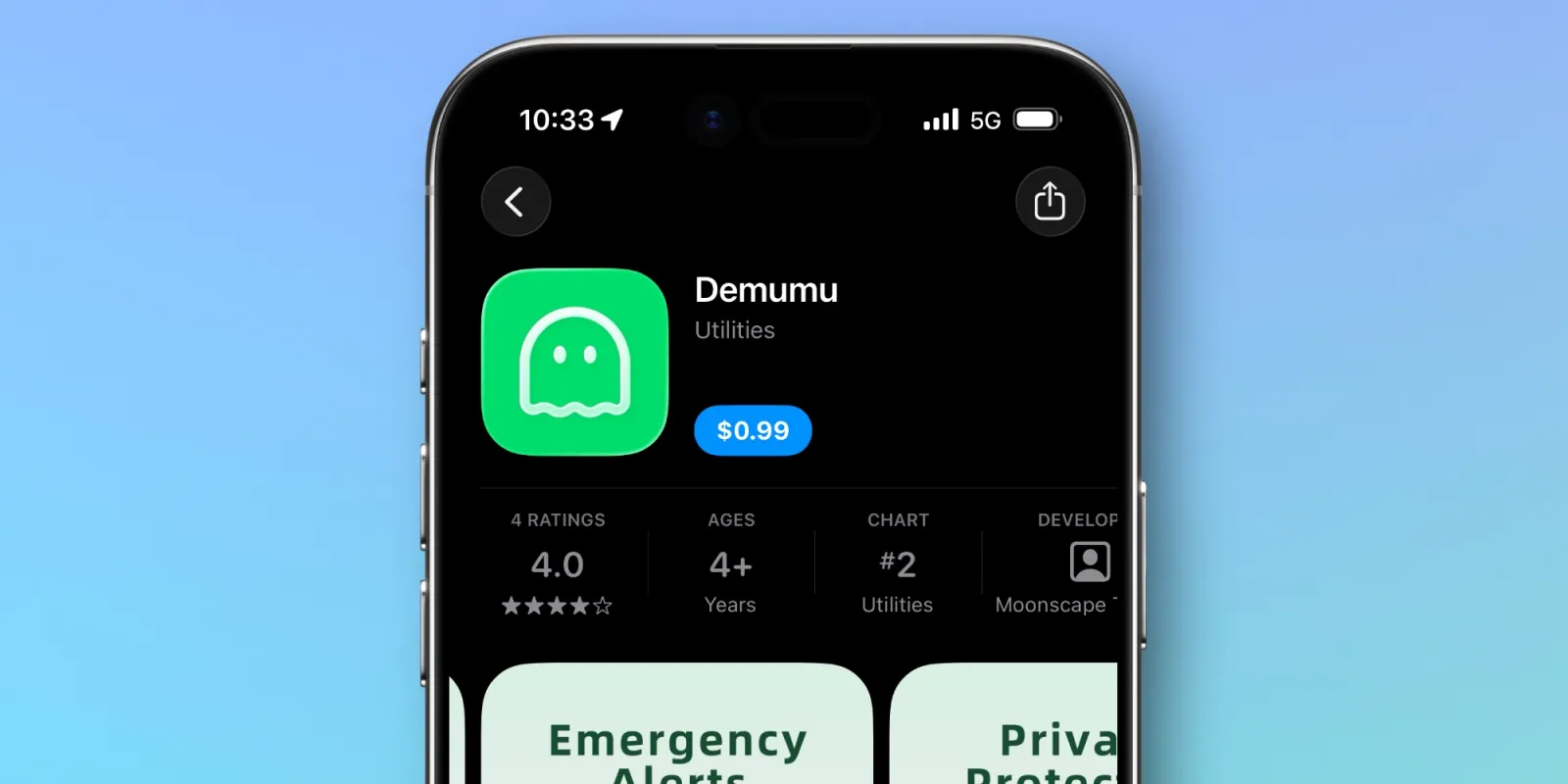

The crying horse is not the only cultural artefact capturing China’s collective unease. In early January, a mobile app with an unusually blunt premise shot to the top of Apple’s paid App Store charts in China.

Its name was startling: “Are You Dead?”

Known in Mandarin as Sileme, the app was developed by Beijing-based startup Moonscape Technologies. Its function was simple but unsettlingly direct. Users living alone were asked to confirm their safety once a day by tapping a large green button. If the user failed to check in for 48 hours, the app automatically sent an email alert to a designated emergency contact.

The idea was born from personal experience. Ian Lü, one of Moonscape’s co-founders, said that all three founders had spent time living alone in major Chinese cities.

“We realized that if anything happened to us, nobody would have known,” Lü told CNBC. “So we created the app for users to alert their family or friends.”

Originally launched as a free service, the app introduced a subscription fee of 8 yuan per month (about US$1.15 or €1) to cover rising operational costs. It quickly surged to become the top paid app in China during the first week of January.

A Country Living Alone—By the Millions

The app’s popularity is closely tied to a profound demographic shift underway in China. Living alone is no longer an exception; it is becoming a defining feature of modern urban life.

According to estimates cited by state media and the Global Times, China may already have up to 200 million one-person households, with a solo living rate exceeding 30 percent. A report from the Beike Research Institute projects that the number of people living alone could reach 150 million to 200 million by 2030.

Several forces are driving this trend. China’s population is ageing rapidly, leaving more elderly citizens without close family support. At the same time, many younger people who migrate to cities for work have no siblings and increasingly delay—or entirely reject—marriage.

In 2024, China’s marriage rate fell to 4.3 percent, the lowest level in 45 years. That same year, 6.1 million couples married, while 2.6 million couples divorced.

As solo living becomes more common, everyday infrastructure is quietly adapting. Single-person dining cubbies at McDonald’s—partitioned seats designed for customers eating alone—have gone viral on Chinese social media. Though not new, their sudden popularity reflects how visible solitary living has become.

When Lonely Deaths Become National Debates

The fears that the “Are You Dead?” app addresses are not abstract. In December, a case in Shanghai reignited public discussion about what it means to die alone.

Jiang Ting, a 46-year-old woman living by herself in Hongkou district, died after a short illness. Quiet and private, she was rarely seen by neighbours except when commuting or collecting takeaway food. With her parents deceased and no partner or children, Jiang had no next of kin to inherit her estate. Her death went unnoticed for some time, prompting media debate about how Chinese society should handle an increasing number of solitary deaths.

For Xiong Sisi, a professional in her 40s who also lives alone in Shanghai, the story struck close to home.

“I truly worry that, after I die, no one will collect my body,” she said. “I don’t care how I’m buried, but if I rot there, it’s bad for the house.”

When Xiong later read about the viral app, she immediately saw its appeal. She shared the article in a WeChat group with five fellow childless friends. “I said: ‘This is actually quite practical.’”

Why the App Struck a Chord—Especially With Women

The app’s rise was fuelled in part by RedNote, a social platform predominantly used by women. Its tongue-in-cheek name—a play on Eleme, China’s ubiquitous food delivery app “Are You Hungry?”—helped it spread rapidly.

“This app makes people feel alive,” one RedNote user wrote. Others described it as a phenomenon that both reflects and combats the loneliness of modern urban life.

While loneliness affects all demographics, analysts suggest the app tapped into anxieties felt particularly strongly by young Chinese women. China’s declining marriage rate is largely driven by women, many of whom reject traditional expectations of subservience in relationships. Tech analyst Ivy Yang describes this trend as “feminism with Chinese characteristics,” or “RedNote feminism.”

Choosing independence can be liberating—but it can also widen emotional gaps that technology increasingly seeks to fill. Yang calls this emerging market the “loneliness economy”, pointing to the growing popularity of AI companions and virtual “AI boyfriends,” especially among women.

Work, Involution, and Urban Isolation

Economic pressures intensify these emotional strains. For decades, China’s growth relied on massive internal migration as people left hometowns to seek opportunity in megacities. While financially transformative, this movement has left deep psychological scars.

Writer Xiao Hai, once a factory worker in Shenzhen, described his experience as a migrant in stark terms: a loneliness that “submerged through to the concrete floor beneath my feet.”

Clinical psychologist George Hu, president of the Shanghai International Mental Health Association, says the effects of urban isolation in China are amplified by scale and intensity.

“There is not only isolation but anxiety, stress and a sense of helplessness,” Hu explains.

He points to China’s infamous “996” work culture—working from 9am to 9pm, six days a week—as a major contributor, especially when long hours no longer guarantee milestones such as home ownership or financial security.

This sense of futility is captured by another buzzword: “involution”—the feeling of working harder than ever for diminishing returns.

From Safety Tool to Political Sensitivity

Despite its popularity, the “Are You Dead?” app soon encountered resistance.

State media criticised its name as morbid and inauspicious. In response, Moonscape Technologies announced plans to adopt a global brand name: Demumu, a blend of “death” and a cutesy suffix associated with popular Chinese toy trends.

But the controversy did not end there.

Soon after its rebranding, the app disappeared from China’s Apple App Store. Apple later confirmed that China’s cybersecurity watchdog ordered its removal for failing to comply with rules requiring apps to “adhere to public order and good morals.”

“The app remains available for download on all other storefronts where it appears,” Apple said in a statement.

News articles about the app were subsequently censored, and Moonscape warned users about counterfeit versions circulating online. Lü said it was “not convenient” to discuss the exact reasons for the takedown, though analysts suggest regulators may have viewed the app as promoting superstition or social pessimism.

A Global Phenomenon, Not Just a Chinese One

Ironically, as the app vanished from China’s App Store, it gained traction abroad. Listed internationally as Demumu, it rose into the top two paid utility apps in the United States, Singapore, and Hong Kong, driven largely by Chinese immigrant communities.

Loneliness, after all, is not uniquely Chinese. The World Health Organization identifies social isolation as a major risk factor for poor mental health and mortality among older people. In Europe, a 2022 EU survey found that over one-third of Europeans feel lonely, while 2024 data shows more than 75 million single-adult households without children.

“I feel what is being reflected is not just the situation in China,” Lü said. “This new ‘living alone’ group is a global phenomenon.”

What Comes Next?

Despite regulatory hurdles, Lü remains ambitious. He hopes to develop a sister app for elderly users and integrate AI features capable of detecting dangerous situations—such as sudden movement or abnormal behaviour—and alerting contacts earlier.

Mental health professionals see promise in the concept but caution against oversimplification. Hu believes future versions should allow users to signal distress before emergencies occur. “I’d like a way to say: ‘I’m alive, but I need help.’”

A Crying Horse, a Disappearing App, and a Nation at a Crossroads

Together, the crying horse plushie and the “Are You Dead?” app form an unlikely but telling portrait of modern China. One is soft, silent, and symbolic; the other digital, blunt, and controversial. Both resonate because they speak to shared anxieties—economic uncertainty, social isolation, and a yearning to be seen.

As growth slows and traditional social structures loosen, Chinese society is searching for new ways to cope. Sometimes, that search takes the form of a toy that cries for you. Sometimes, it’s an app that asks a question few want to answer—but many are afraid to ignore.

And in that quiet fear lies one of the most revealing stories of China today.

With inputs from agencies

Image Source: Multiple agencies

© Copyright 2025. All Rights Reserved. Powered by Vygr Media.