In the geopolitical heartland of Central Asia, a quiet but seismic shift is underway. China, once a peripheral player in the former Soviet republics of the region, is now overtaking Russia in trade, infrastructure, diplomacy, and—most strikingly—military influence. As Moscow remains mired in its prolonged war in Ukraine, Beijing has seized the opportunity to expand its economic footprint, deepen political ties, and even establish a presence in the region’s arms markets. While this may appear as a win for multipolar cooperation between the two Eurasian giants, it raises a deeper question: Is Russia losing Central Asia to China, and could this transformation eventually test the limits of their strategic friendship?

A New Silk Road: Infrastructure and Trade Shift the Power Balance

China’s inroads into Central Asia are far more than symbolic. The second China–Central Asia Summit, held recently in Astana, Kazakhstan, was laden with significance. Not only did President Xi Jinping pledge deepened cooperation in trade, infrastructure, and energy, but he also signed a formal treaty of “permanent good-neighbourliness and friendly cooperation” with the five Central Asian nations—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan.

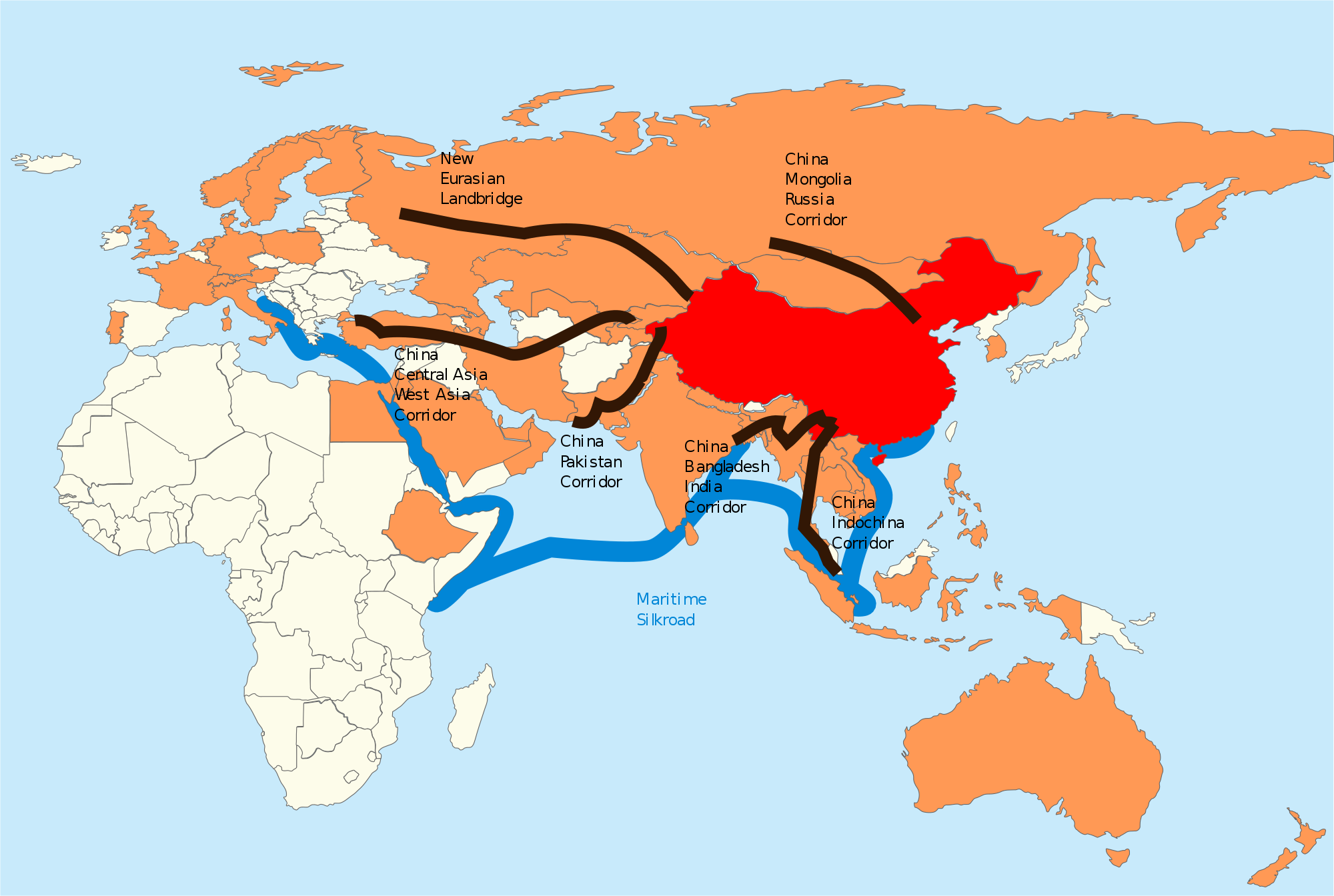

Beijing’s approach has been methodical and strategic. Through its flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China is reshaping the region’s connectivity landscape. Infrastructure projects once delayed due to Russian opposition—such as the long-anticipated China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan railway—are now progressing rapidly. This railway, while technically challenging due to differing track gauges and ageing infrastructure, symbolises a deeper reality: Moscow’s veto power in Central Asia is fading.

In 2023, China overtook Russia to become Central Asia’s largest trading partner, with bilateral trade reaching a record $94.8 billion. In just the first five months of the following year, trade between China and the five Central Asian nations grew another 10.4%, reaching 286.42 billion yuan (~$40 billion USD). Economically, the region is slipping into China's orbit—and Chinese commentators are not shy about calling it a "silent metamorphosis."

From Economic Expansion to Energy Domination

China's influence doesn't stop at trade and transport. Energy cooperation is another key area where Beijing is eclipsing Moscow.

Turkmenistan, the largest supplier of natural gas to China, remains the only Central Asian nation with a trade surplus with Beijing. Xi Jinping has explicitly called for an expansion of this relationship, along with a deeper exploration of mineral and agricultural cooperation. Notably, China rejected Russia’s proposal to route the Power of Siberia 2 gas pipeline through Kazakhstan. Instead, it has pursued a more direct route, further emphasising its desire to diversify energy supplies and reduce reliance on Russian gas.

This rejection is emblematic of a broader shift: China is not only establishing itself as the dominant economic force in Central Asia but is also actively reshaping regional energy dynamics to its advantage.

The Arms Market: China Moves In As Russia Bows Out

Perhaps the most telling—and surprising—development is China’s rapid entry into Central Asia’s arms market, a domain long monopolised by Russia.

Historically, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan depended almost entirely on Russian military hardware. But with Moscow’s defence industry stretched thin by the war in Ukraine—where it has had to rely on arms imports from Iran and North Korea—Russia’s ability to fulfil international arms contracts has plummeted. Between 2020 and 2024, Russian arms exports fell by 64%, a massive contraction that opened the door for Beijing.

China, sensing an opportunity, has filled the void. Kazakhstan purchased Chinese drones in 2024, and Uzbekistan is reportedly negotiating for JF-17 fighter jets—a cost-effective, multi-role aircraft co-produced by China and Pakistan. Uzbekistan has also unveiled Chinese-made air defence systems such as the FM-90 and KS-1C, while Tajikistan has deployed the HQ-17 AE system. Turkmenistan, too, has acquired an array of Chinese military hardware, including the long-range HQ-9 air defence system and several advanced radar and drone technologies.

This strategic shift in arms procurement signifies more than just a change in vendor preference—it marks a tectonic realignment in security affiliations across Central Asia.

Cultural Realignment: De-Russification and the Rise of the RMB

Central Asia’s pivot towards China is not limited to economics and security—it is also deeply cultural. The post-invasion era has seen a steady push for “de-Russification.” Native languages are now prioritised over Russian in schools, and even Chinese is gaining traction as a preferred foreign language. Cultural life is increasingly oriented away from Soviet legacies and toward regional and Asian identities.

Financially, the renminbi (RMB) is gaining prominence. With expanded investment in digital infrastructure and increased RMB-based trade settlements, China is positioning itself not just as a regional partner but as a rule-setter. In markets across the region, Chinese goods are replacing Russian imports—another subtle but important indicator of shifting loyalty.

Beijing’s Narrative: Cooperation, But Not Equality

China’s official rhetoric remains predictably diplomatic. President Xi’s speeches emphasise “win-win cooperation,” “shared destiny,” and “harmonious development.” Yet, beneath this language lies a carefully calculated narrative of strategic superiority. Chinese media headlines have openly declared: “The five Central Asian countries are striving to shake off the shadow of Russia.” Some analysts go further, suggesting that Russia’s loss is a necessary tradeoff for China's rise as the new regional hegemon.

Significantly, China is conducting much of this diplomacy outside of traditional Russia-led frameworks like the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). Instead, it has fostered the C5+1 format, engaging bilaterally and multilaterally with Central Asian states without Russia. This signals a desire to build a regional order where Moscow plays second fiddle.

Strained Friendship? Russia and China on Diverging Paths

While Beijing and Moscow publicly maintain a front of strategic alignment—particularly in their shared opposition to NATO and U.S. hegemony—their competition in Central Asia could become a litmus test for the durability of their partnership.

Will this growing Chinese dominance strain the “no-limits” friendship they declared in 2022? Could Russia, bruised and cornered by the West, eventually view Beijing’s moves not as partnership but encroachment? These questions are becoming increasingly difficult to ignore.

Already, Russia has attempted to push back with large-scale military drills in the region and new proposals for regional security frameworks, including “military exclusion zones.” But these efforts appear reactive rather than proactive—desperate moves to reclaim shrinking influence.

The Future of Central Asia—and Sino-Russian Relations

What we are witnessing in Central Asia is not merely a regional rebalancing; it is a microcosm of global power shifts. Russia, distracted by its war and weakened by sanctions, is losing its historic backyard. China, meanwhile, is emerging not just as a partner, but as the de facto leader in the region—economically, diplomatically, and militarily.

For the Central Asian republics, this shift offers new opportunities: diversification of partnerships, modern infrastructure, and access to capital. But it also brings new dependencies—this time on Beijing.

For Russia and China, the stakes are far higher. As Beijing fills the void left by Moscow, the balance of power in their alliance is tilting sharply. The question now is not whether China can replace Russia in Central Asia—it already is—but whether this quiet conquest will eventually rupture the fragile friendship between two of the world’s most powerful autocracies.

Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Vygr’s views.

With inputs from agencies

Image Source: Multiple agencies

© Copyright 2025. All Rights Reserved Powered by Vygr Media.