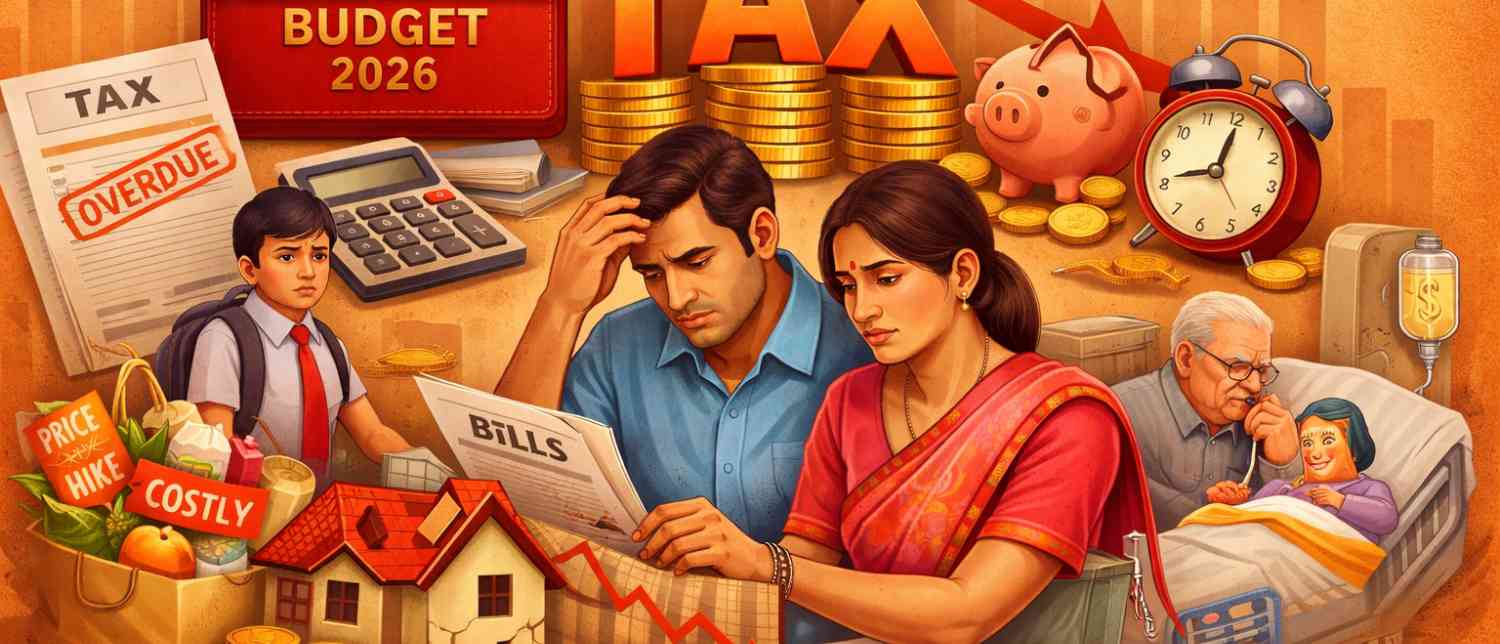

Budget 2026 as a flashpoint for the middle class — expectations vs reality, viral moment, consumption anxiety

For over a decade, India’s economic story has rested on a simple but powerful pillar: household consumption. More than 55–60% of India’s GDP is driven by what families spend—on homes, education, healthcare, transport, food, and the occasional aspiration. At the heart of this engine sits the urban middle class, whose purchasing power has quietly sustained growth even when private investment stalled and exports faltered.

Budget 2026 was therefore not just another fiscal statement. For millions of salaried households navigating stagnant wages, rising living costs, job insecurity, healthcare expenses, and shrinking savings, it was expected to offer recognition—if not relief. Instead, what emerged was a Budget that exposed a deeper truth: India’s middle class is being asked to shoulder a growing share of the tax burden while receiving limited structural support in return.

The result is not merely disappointment. It raises fundamental questions about fairness, consumption-led growth, and the sustainability of India’s current tax model.

No Direct Relief, Many Indirect Pressures

At first glance, Budget 2026 offered little by way of headline tax relief. Income tax slabs and rates for FY 2026–27 were left unchanged. The standard deduction remains frozen at ₹2.75 lakh, despite years of inflation and rising urban expenses. Expectations of a higher rebate threshold or an expanded deduction—especially after tax-free income was raised from ₹7 lakh to ₹12 lakh last year—were firmly set aside.

This inaction stung because urban households are spending far more today on essentials that the tax system largely ignores: housing rents or EMIs, private education, healthcare, commuting, and elder care. RBI consumer confidence surveys already point to growing anxiety around prices, job security, and shrinking discretionary spending, particularly among white-collar professionals in services and technology who face income volatility and layoffs.

But beyond what the Budget did not do, what it did do may quietly squeeze middle-class finances even further.

Seven Budget Changes That Will Hurt the Middle Class

Several proposals announced by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman will directly or indirectly raise costs for salaried taxpayers from April 1, 2026.

-First, trading in derivatives has become more expensive. The Securities Transaction Tax (STT) on futures has been increased from 0.02% to 0.05%. On options, the STT on premium has risen from 0.1% to 0.15%, while the STT on exercise of options has gone up from 0.125% to 0.15%. For retail investors and active traders—many of whom turn to derivatives to supplement income or hedge risks—this directly raises transaction costs.

-Second, taxation of Sovereign Gold Bonds (SGBs) has changed. While the capital gains exemption on redemption at maturity continues for bonds bought in the primary market during government issuance, investors who purchased SGBs from the secondary market will now face capital gains tax at maturity. As CA Avinash Kumar Rao of Mohindra & Associates explains, long-term capital gains will be taxed at 12.5%, and short-term gains at slab rates, along with surcharge and cess. For many middle-class savers who bought SGBs for safety and tax efficiency, post-tax returns will now be lower.

-Third, disability pension tax relief has been withdrawn for defence personnel retiring on superannuation. Going forward, only those invalided out of service due to bodily disability attributable to or aggravated by military service will be eligible for the exemption. This narrows the scope of relief that earlier extended to a broader set of retirees.

-Fourth, share buybacks will now be taxed as capital gains in the hands of all shareholders to curb tax arbitrage. Corporate promoters will face an effective tax of 22%, while non-corporate promoters will be taxed at around 30%. While reverting buyback taxation to capital gains offers some clarity, it still reshapes post-tax outcomes for investors.

-Fifth, alcohol is likely to become costlier. The Tax Collected at Source (TCS) rate on the sale of alcoholic liquor for human consumption has been proposed to increase from 1% to 2%, raising upfront tax outflows for distributors and retailers, costs that are likely to be passed on to consumers.

-Sixth, a less noticed but critical change affects investors who use borrowed funds. The Budget removes the deduction for interest expenditure incurred against dividend income or income from mutual funds. Earlier, such interest costs could partially offset taxable income within limits. Now, leveraged investing—often used by small investors—becomes less attractive as post-tax returns fall.

-Finally, even office coffee may cost more. The withdrawal of customs duty concessions on imported coffee roasting, brewing, and vending machines raises effective duties by around 2.5%, compounded by currency pressures. Industry executives warn that this will eventually show up in café and pantry prices.

Individually, these changes may seem marginal. Together, they reinforce a pattern: the middle class pays more at multiple touchpoints of daily life.

The Viral “Aww” and a Deeper Disconnect

Public frustration crystallised in a moment that went viral. During a post-Budget press conference, when a journalist asked Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman what the Budget offered the middle class, she paused, smiled faintly, and shifted the conversation to university townships. Her brief “awww” reaction triggered a meme fest online.

Comments ranged from biting sarcasm—“Oooo… hum to bhool hi gaye ki middle class exist karti hai”—to pointed questions about definitions of the middle class in a country where average annual income is around ₹2.5 lakh. The body language, many felt, said more than the speech.

This episode resonated because it reflected a wider sentiment: that the middle class is visible mainly as a source of revenue, not as a constituency deserving policy imagination.

What the Budget Did Offer—And Why It Feels Insufficient

To be fair, Budget 2026 did include selective relief measures. The TCS rate on overseas tour packages has been reduced to a flat 2%, down from earlier slabs of 5% and 20%. Similarly, remittances under the Liberalised Remittance Scheme for education and medical purposes now attract just 2% TCS, easing cash-flow pressures for families funding overseas studies or treatments.

Interest awarded by Motor Accident Claims Tribunals has been exempted from income tax, and the requirement for TDS on such interest has been removed—an important relief for accident victims.

The rollout of the Income Tax Act, 2025, effective April 1, 2026, promises simplified rules and redesigned return forms to help ordinary taxpayers file without professional assistance. Deadlines for revised and belated returns have been extended to March 31, while filing dates for non-audit cases and trusts move to August 31. Minor tax defaults have been decriminalised, reducing the threat of prosecution for technical lapses.

On the cost side, customs duty exemptions on 17 cancer drugs and medicines for rare diseases aim to reduce treatment expenses. Tariffs on dutiable personal imports have been cut from 20% to 10%, and baggage rules for international travellers are being liberalised.

The government has also allocated ₹22,000 crore to the PM Surya Ghar Muft Bijli Yojana to promote rooftop solar adoption, potentially lowering electricity bills. Education and skills initiatives include girls’ hostels in every district for STEM students, training 1.5 lakh caregivers in geriatric care, and upskilling 10,000 tourist guides.

Yet for many middle-class households, these measures feel peripheral to the core problem: disposable income.

Consumption Is the Economy—and It Is Under Strain

India is not an export-led economy like China. Domestic demand drives growth. Private Final Consumption Expenditure accounted for 61.5% of GDP in the first half of FY 2025–26. With private investment stuck at around 12% of GDP for nearly a decade, consumption has carried the economy.

But consumption depends on real incomes. Between 2019 and 2024, nominal wage growth of 1–5% failed to keep pace with inflation, eroding purchasing power. Rising healthcare costs, private education fees, and commuting expenses further strain household budgets.

The market reaction to Budget 2026 was telling. The Nifty 50 fell 2.33%, and the Sensex plunged over 1,500 points. This was not just investor disappointment; it reflected concerns about weakening domestic consumption.

The Tax Burden Is Shifting—And It’s Not Subtle

India’s tax structure reveals a troubling trend. Personal income tax collections are rising faster than corporate taxes. For the first time, personal income tax has overtaken corporate income tax as a share of direct taxes.

Projections show personal income tax contributing ₹14.66 lakh crore, or 27.4% of central government receipts, by FY 2026–27, up from ₹12.35 lakh crore. Corporate tax collections, meanwhile, are expected to rise to ₹12.31 lakh crore. Personal taxes will be 18% higher than corporate taxes.

This is happening despite the fact that only about 4.8% of Indian adults pay income tax. An even smaller group—around 0.3%—accounts for roughly 76% of personal income tax receipts. Over 90% of income tax returns are filed by salaried middle-income earners, whose taxes are deducted at source, leaving little room for planning.

In contrast, corporate tax rates have fallen from 30% to 22% for domestic firms and 15% for new manufacturers. Corporate tax collections declined from 3.5% to 2.8% of GDP even as profits surged. In 2023–24, listed company profits rose 22.3%, while employment grew just 1.5%.

Indirect taxes compound the burden. GST collections have more than doubled in five years, reaching ₹22.08 lakh crore. Household consumption surveys show that the bottom 50% of urban consumers and the middle 30% each bear about 29–30% of the GST burden, while the top 20% carry around 41%. This means middle-income households shoulder nearly as much consumption tax as the lower half.

LocalCircles surveys suggest that GST 2.0 has not delivered meaningful relief on essentials like food and medicines. Any tax cuts appear to have been absorbed by supply chains rather than passed on to consumers.

Paying Like an OECD Country, Living Without OECD Protections

India’s tax trajectory increasingly resembles advanced economies—but without their safeguards. In OECD countries, personal income tax contributes around 8% of GDP. In India, it is about 3.5%, drawn largely from the salaried middle class. Indirect taxes make up around 45% of total tax revenue in India, compared to 30–35% in OECD nations.

The difference lies in what taxpayers get in return. OECD countries fund universal healthcare, education, pensions, and childcare through taxes. India spends just 1.9% of GDP on health and 2.7% on education, with total social sector spending at 7.6% of GDP. Parliamentary committees have flagged that India even lags some SAARC neighbours in education spending.

As a result, the middle class pays more in taxes and GST, yet still finances healthcare, education, and retirement privately. Household savings have fallen from over 20% to 18.1% of GDP. Net financial savings are at a 47-year low of 5.1%, while household debt has surged to 41.9% of GDP—much of it funding daily consumption rather than assets.

An Unsustainable Equation

Budget 2026 reflects a calibrated, fiscally cautious approach. But it also exposes an unsustainable equation: asking the middle class to fund growth, welfare, and fiscal discipline without expanding the tax base at the top or meaningfully reducing indirect burdens at the bottom.

India’s Constitution promises economic justice. Article 38 directs the state to reduce inequalities of income and wealth. Yet wealth taxes have been abolished, inheritance taxes eliminated, and capital income continues to enjoy favourable treatment. The top 1% now owns over 40% of national wealth, while the bottom 50% holds just 3%.

Without correcting this imbalance, consumption-led growth will weaken. The middle class cannot indefinitely absorb rising taxes, inflation, and stagnant wages.

Budget 2026 may not have broken the middle class. But it has reinforced a message they already feel: they are paying more, getting less, and being asked to carry India’s economy quietly—without applause, and increasingly, without relief.

*Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Vygr’s views.

With inputs from agencies

Image Source: Multiple agencies

© Copyright 2025. All Rights Reserved. Powered by Vygr Media.