Kerala, often hailed as a model state for its healthcare system, is now grappling with a public health emergency that has sparked fear and confusion across its districts.

Kerala is facing an alarming public health emergency after a sudden surge in Primary Amoebic Meningoencephalitis (PAM) cases—an infection caused by Naegleria fowleri, popularly known as the “brain-eating amoeba.”

In the past nine months, the state has reported 69 confirmed cases and 19 deaths, including a four-month-old baby. Nine of these deaths occurred in just one month, triggering statewide panic and raising urgent questions about the spread of this rare but deadly disease. It is affecting individuals as young as three months to as old as 91 years.

While the global fatality rate for PAM exceeds 90 percent, Kerala has managed to keep it under 30 percent, thanks to early detection and proactive health interventions. Still, the rising number of cases has forced authorities into emergency mode, as the infection continues to spread across districts in unpredictable patterns.

What Is the ‘Brain-Eating Amoeba’?

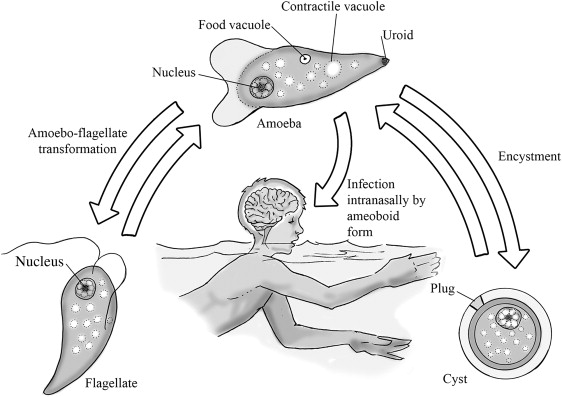

Naegleria fowleri is a free-living amoeba—a unicellular organism that thrives in warm freshwater environments like lakes, rivers, ponds, and hot springs. It can also survive in inadequately chlorinated swimming pools and contaminated water tanks.

The amoeba earns its frightening nickname because it destroys brain tissue after it enters the human body, not through drinking water but through the nose—often while swimming, diving, or bathing in contaminated freshwater. From there, it travels to the brain via the olfactory nerves, causing severe damage to brain tissue and triggering Primary Amoebic Meningoencephalitis, a rapidly progressing and often fatal infection.

How the Infection Spreads

Unlike many waterborne diseases, PAM does not spread through drinking contaminated water or from person to person. The only route of infection is when water containing Naegleria fowleri enters the nose.

From there, the amoeba moves swiftly to the brain, triggering aggressive inflammation. This makes swimming, diving, or bathing in stagnant freshwater the riskiest activities.

Symptoms That Shouldn’t Be Ignored

The early symptoms of PAM resemble those of bacterial meningitis, making timely diagnosis difficult. They usually appear within 1–9 days after exposure and worsen rapidly.

Early Signs:

-

Headache

-

Fever

-

Nausea and vomiting

Advanced Symptoms:

-

Stiff neck

-

Confusion

-

Seizures

-

Coma

According to medical experts, most patients die within 5 days of symptom onset, though the disease can claim lives in as little as 1–18 days. As health experts warn, timely detection is critical, but unfortunately, most cases are diagnosed too late for effective treatment.

Kerala’s Current Situation

Kerala first reported cases of PAM in 2016, and until 2023, only eight cases had been confirmed in the state. But the trend has escalated dramatically. Last year alone, Kerala saw 36 cases and nine deaths. In 2025, the numbers nearly doubled, with 69 cases and 19 deaths reported already within 9 months.

Unlike earlier outbreaks, where clusters were linked to specific water sources, the current wave is spread across districts, making containment difficult. As Health Minister Veena George explained, “Unlike last year, we are not seeing clusters linked to a single water source. These are single, isolated cases, and this has complicated our epidemiological investigations.”

Patients affected range widely in age, further complicating the picture. Cases have included infants with minimal water exposure as well as elderly individuals, raising serious questions about how far-reaching the risk may be.

Age Groups at Risk

Contrary to earlier assumptions that the infection mainly affected children and young adults, Kerala’s cases span a wide range—from a 3-month-old infant to a 91-year-old patient.

This broad distribution suggests that everyone is vulnerable, regardless of age or previous health conditions.

Political Storm in the Assembly

The outbreak has also sparked heated political debate. In the Kerala Legislative Assembly, Opposition MLA N. Shamsudheen from Palakkad accused the government of failing to address the crisis effectively.

“The government has failed to understand the source and prevent the infection. The government is just saying that the fatality rate is low in Kerala,” he said.

In response, Health Minister Veena George defended the state’s efforts, arguing that misinformation was clouding the issue. She highlighted Kerala’s relatively lower fatality rate compared to the global average and emphasized ongoing preventive strategies.

According to George, Kerala began formally notifying all meningoencephalitis cases in 2023, after facing a Nipah virus outbreak, to better trace their causes. She also revealed that PCR testing facilities, previously limited to Chandigarh and Puducherry, are now available in Thiruvananthapuram, with another center being set up in Kozhikode.

“Kerala was the first state in India to prepare guidelines on the infection, which are available to the public,” she added.

Experts Weigh In

- Health Minister Veena George

Kerala’s Health Minister Veena George has admitted that the state is grappling with a “serious public health challenge.” She highlighted that unlike in previous years, cases are not confined to clusters or specific water sources.

“Unlike last year, we are not seeing clusters linked to a single water source. These are single, isolated cases, and this has complicated our epidemiological investigations,” she said.

George also defended the state’s health system against opposition criticism, emphasizing Kerala’s success in keeping the fatality rate significantly lower than the global average:

“Early detection of the brain eating amoeba has helped Kerala keep fatalities under 30 percent, when the global average is 97 percent,” she noted.

- Dr Aravind R, Infectious Diseases Specialist

Dr Aravind R, head of the Infectious Diseases Department at Government Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram, explained that the Kerala Public Health Act has been invoked to launch preventive measures.

“As it emerges that perhaps all waterbodies—wells, ponds, canals, swimming pools, water theme parks—could be a potential source of amoebic infection for people using them, (they need to be) regularly cleaned and maintained in good condition, and we are doing everything to ensure that they do not lead to infections,” he said.

- Dr Sudhir Kumar, Neurologist

Hyderabad-based neurologist Dr Sudhir Kumar warned that the risk of infection is wider than previously assumed:

“What makes it even more worrying is that some patients had no obvious exposure to ponds or swimming pools, and a few infants were affected despite minimal exposure. These features suggest the infection risk is wider and more unpredictable than previously believed,” he said.

- Dr Rajeev Jayadevan, Gastroenterologist

Dr Rajeev Jayadevan, researcher and gastroenterologist, reminded that India’s first two cases of PAM were recorded in 1971 in West Bengal, when doctors discovered Naegleria fowleri in spinal fluid samples from infected children.

Climate Change Connection

One of the most worrying findings comes from a Kerala state health department document, which notes that the brain-eating amoeba is a thermophilic organism—it thrives in warm environments. Rising temperatures caused by climate change, combined with an increase in recreational water use during hot weather, are believed to be fueling the outbreak.

The amoeba also feeds on cyanobacteria, which flourish in warmer waters. “Climate change raising the water temperature and the heat driving more people to recreational water use is likely to increase the encounters with this pathogen,” the document warns.

Experts also suggest that global warming may be expanding the geographical range of Naegleria fowleri. Many PAM cases in Kerala were reported soon after spikes in air temperature, hinting at a direct correlation.

Rising global temperatures have two major effects:

-

Expansion of Amoeba’s Habitat: Increasing water temperatures allow Naegleria to spread into new geographical areas.

-

Higher Human Exposure: Hotter weather drives more people to ponds, lakes, and swimming pools, increasing infection risks.

Studies show that many PAM cases occur shortly after spikes in air temperature, suggesting a direct link between climate change and outbreaks.

Why Treatment Is So Difficult

Treatment for PAM is notoriously difficult. Survivors over the last six decades were almost always diagnosed before the infection reached the brain. Once brain swelling develops, the disease is usually fatal.

An “antimicrobial cocktail” remains the only therapeutic option, but its effectiveness hinges on early detection. “This shows that early diagnosis of PAM and timely initiation of an antimicrobial cocktail might be lifesaving,” states the health department’s document.

Early PCR testing can confirm infection, but until recently, such facilities were only available in Chandigarh and Puducherry. Kerala has now set up its own centers in Thiruvananthapuram and Kozhikode.

However, rarity of the disease, rapid progression, and lack of immediate diagnostic tools have hampered research into effective drug regimens. The Kerala government has urged citizens to seek immediate medical help if they develop symptoms resembling meningitis after freshwater exposure.

Government Measures in Kerala

Kerala has become the first state in India to draft official guidelines on PAM. These are publicly available and detail both prevention and treatment strategies.

Key initiatives include:

-

Setting up testing centers within the state.

-

Conducting environmental sampling to detect contaminated water sources.

-

Running public awareness campaigns across schools, communities, and media outlets.

-

Mandating the cleaning and chlorination of water bodies like wells, tanks, and swimming pools.

How to Stay Safe: Prevention Tips

Health authorities stress that prevention is the strongest defense against PAM.

Dos:

-

Avoid swimming or diving in stagnant freshwater ponds, lakes, or canals.

-

Use nose clips when swimming in freshwater.

-

Regularly clean and chlorinate water tanks, swimming pools, and wells.

-

Seek immediate medical help if symptoms appear after freshwater exposure.

Don’ts:

-

Do not allow untreated water to enter your nose.

-

Do not assume drinking water contamination causes infection—it does not.

Kerala’s Past to Present Journey with PAM

The first documented cases of Naegleria fowleri in India were in 1971, when children in West Bengal presented symptoms of brain infection but survived. In Kerala, however, the first case was detected only in 2016. Between then and 2024, 37 cases were reported, with 13 deaths. But in just one year, the numbers have surged dramatically—showing nearly a 100 percent spike between 2023 and 2025.

This sudden rise underscores how changing environmental conditions, coupled with diagnostic challenges, have created a perfect storm for the spread of this deadly disease.

Looking Ahead

As Kerala battles the deadly brain-eating amoeba, the situation highlights not only the importance of swift medical intervention but also the growing impact of climate change on infectious diseases. With the infection spreading unpredictably, affecting infants and the elderly alike, prevention is now the state’s strongest defense.

State health officials are working to increase testing capacity, raise awareness, and enforce safety measures around water bodies. But with fatalities mounting, the call for vigilance among citizens has never been stronger.

The “brain-eating amoeba” may be rare, but its fatal potential is undeniable. For Kerala, every preventive step—be it avoiding stagnant waters, using nose clips, or seeking early treatment—can mean the difference between life and death.

With inputs from agencies

Image Source: Multiple agencies

© Copyright 2025. All Rights Reserved. Powered by Vygr Media.