Indian cinema, particularly Bollywood, has always been more than just a source of entertainment. It is a cultural touchstone, shaping public imagination both within India and abroad. But with this influence comes responsibility—and time and again, Bollywood has faltered in representing India’s diverse cultural landscape. From exaggerated accents to clichéd food references, Indian films have too often relied on stereotypes to depict different communities. Whether it’s South Indians with long names and jasmine flowers in their hair, Marathis boxed into vada pav clichés, or Biharis shown as violent and backwards, Bollywood’s narrative toolkit has struggled to move beyond lazy caricatures.

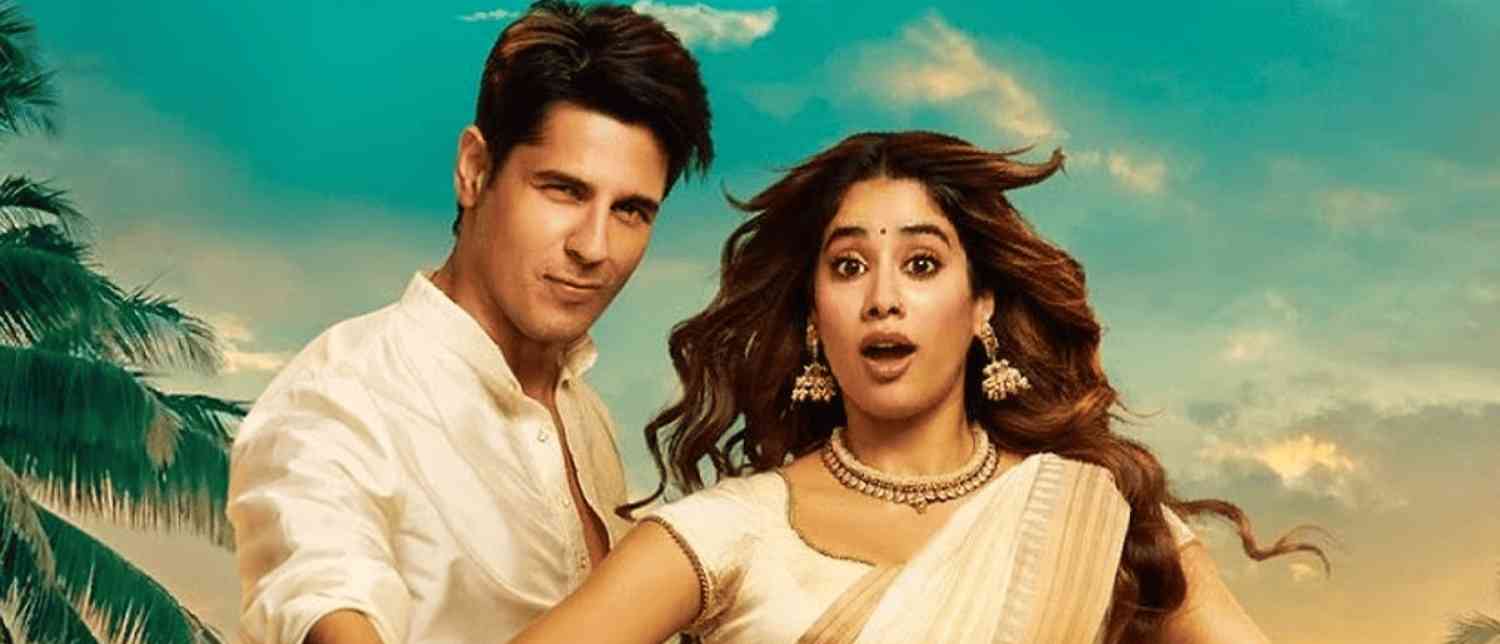

The debate has resurfaced with Param Sundari, a recent romance drama that aspired to bridge the North-South divide but ended up widening it. Instead of celebrating the complexity of South Indian identities, the film fell back on tired tropes. And it isn’t the only one. This persistent problem reflects a deeper pattern in Hindi cinema’s approach to culture—one that demands urgent rethinking.

South Indian Stereotypes: Idlis, Weak Hindi Accents, and Jasmine Flowers in hair

For decades, South Indians in Bollywood films have been stripped of nuance. They are often reduced to broken Hindi, comically long names, coconut, and the ever-present mullapoo (jasmine flowers) in women’s hair. Param Sundari’s character, Thekkapetta Sundari Damodaran Pillai, played by Janhvi Kapoor, embodies this reduction. Her exaggerated name, awkward English, jasmine-adorned hair, and compulsive mocking of North Indians felt less like a real Malayali woman and more like a parody designed for a North Indian gaze.

But the reality of Malayali women today is vastly different. Kerala has some of the highest literacy rates in the country, women are excelling in tech, arts, and academia, and their fashion choices reflect global exposure. By showing them as caricatures, Bollywood erases this diversity and presents a two-dimensional image for mass consumption.

This isn’t new. Deepika Padukone’s exaggerated accent in Chennai Express (2013) turned her Tamil character Meenamma into a punchline rather than a protagonist. In The Kerala Story (2023), Adah Sharma’s Shalini Unnikrishnan carried the same traits—broken English, mullapoo, sarees, and skewed cultural portrayal. Despite receiving national awards, the film was widely criticised for misrepresentation, showing how tone-deaf depictions can still earn institutional validation.

Bollywood also habitually throws in cultural tokens: a Mohiniyattam reference here, a coconut tree backdrop there, and obligatory nods to Rajinikanth and Mohanlal. The effect? South India is flattened into a monolith, while in reality, it comprises diverse linguistic, cultural, and regional identities—Malayalis, Tamils, Telugus, Kannadigas—each with its own history and icons.

Marathis and the Vada Pav Trope

If South Indians get jasmine flowers, Marathis in Bollywood almost always get the vada pav. Characters are routinely shown munching on it, as if it were the only defining feature of Maharashtrian identity. Films like Munna Bhai MBBS (2003) lean into the “tapori” stereotype with slangy Marathi accents and filmi personas, often reducing the community to sidekicks or comic relief.

Serious portrayals exist but still carry undertones of violence or parochialism. Vaastav (1999), starring Sanjay Dutt, explored the underworld of Mumbai with heavy Marathi presence, but in doing so reinforced an association between Marathi men and gangsterism. Similarly, the Shiv Sena-influenced portrayal of Marathi pride in many films positions them as hyperlocal and narrow-minded, rarely as modern cosmopolitans.

This stereotyping also ignores Maharashtra’s cultural richness—from the Warkari spiritual tradition to the state’s contributions to literature, theatre, and progressive politics. Instead of multidimensional characters, Bollywood offers caricatures that reinforce cultural clichés.

Biharis and UPites: Dirty, Backwards, and Violent?

When it comes to UP and Bihar, Bollywood often veers into darker territory. The region is shown as dirty, lawless, and rife with backwards thinking. Films like Gangaajal (2003), while powerful in their critique of corruption and violence, cemented an image of Bihar as synonymous with brutality. More recently, web series like Mirzapur have extended this trope, portraying the Hindi heartland as an endless saga of guns, goons, and patriarchal oppression.

Characters from Bihar or UP in mainstream Hindi films often speak broken Hindi or Bhojpuri-accented Hindi, played for laughs or menace. Rarely do we see aspirational, modern, or cosmopolitan portrayals. Yet, in reality, UP and Bihar have produced some of India’s most celebrated writers, thinkers, and leaders—from Premchand to Jayaprakash Narayan. Bollywood’s limited lens flattens this richness into regressive archetypes.

_1756575578.avif)

Freedom Comes With Responsibility

Defenders of Bollywood’s cultural shorthand argue that films are about entertainment, not accuracy. After all, cinema thrives on dramatisation. But freedom of storytelling comes with responsibility. For millions who have little exposure to regions beyond their own, Bollywood becomes their only window into other cultures. A skewed or caricatured portrayal can distort public perception, sometimes reinforcing prejudice.

Filmmakers could easily avoid this by either casting authentically or by investing time in research and cultural nuance. As one critic observed of Param Sundari, the director could have chosen an actual Malayali actress or at least trained Kapoor to better embody the character. Instead, the film prioritised star power and marketability over cultural truth.

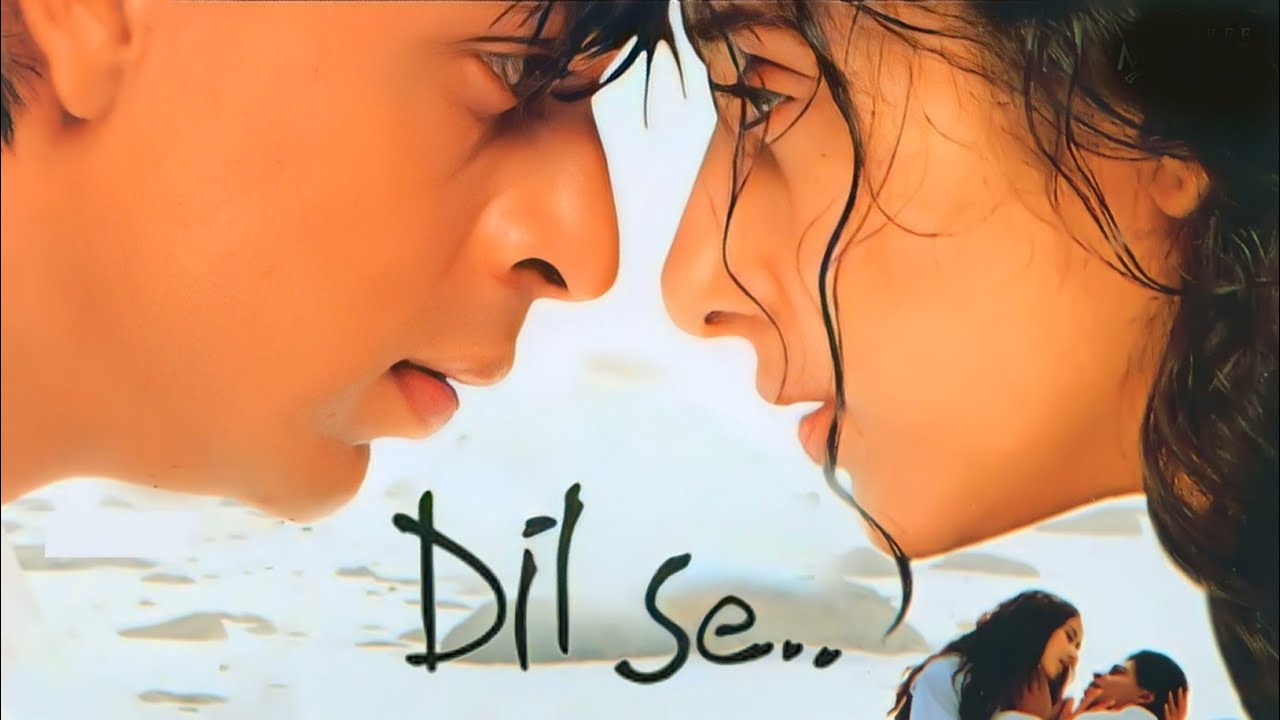

This isn’t about censorship. It’s about respect. Art can be entertaining and authentic at the same time—as seen in films like Dil Se (1998), which presented Manisha Koirala’s South Indian character with dignity, or Karwaan (2018), which explored Malayali identity with warmth and nuance. Bollywood knows how to do it; it simply often chooses not to.

The Manufactured North-South Divide

Beyond individual films, the stereotyping problem is compounded by a growing “North vs South” narrative in popular discourse. Social media platforms amplify this divide, often pitting Bollywood against South Indian industries like Tollywood or Kollywood. Memes, posts, and debates frequently portray the industries as rivals, feeding into regional rivalries.

Scholars argue this isn’t always organic—it’s manufactured. Social media algorithms thrive on conflict and amplify divisive content, subtly shaping public opinion. In some analyses, this manipulation even aligns with broader geopolitical strategies, where external actors benefit from sowing discord within India. The idea is unsettling: the divide we see between Bollywood and South cinema may not be entirely homegrown but encouraged by global digital forces.

Regardless of its origins, the effect is clear. Instead of celebrating Indian cinema as a pluralistic whole, audiences are being nudged into choosing sides, reinforcing regional stereotypes along the way.

The Rise of South Cinema and Bollywood’s Response

Ironically, while Bollywood stereotypes the South, South Indian cinema is steadily dismantling Bollywood’s dominance. Starting with Baahubali (2015 & 2017), followed by blockbusters like KGF, Pushpa, RRR, and Jailer, South Indian films have redefined pan-Indian cinema. Their storytelling, technical brilliance, and unapologetic rootedness have resonated with audiences across India, including the Hindi belt.

This has led to frequent box office clashes: KGF 2 vs Laal Singh Chaddha, Jailer vs Gadar 2, Salaar vs Dunki. More clashes loom, with films like War 2 and Coolie competing with Kantara 2. The result? Bollywood can no longer afford to ignore cultural authenticity. Audiences are rewarding films that feel genuine, even if they come from outside the traditional Hindi cinema power centres.

Why Bollywood Needs to Prep Before It Reps

The persistence of cultural stereotypes reveals a deeper complacency in Bollywood. Instead of doing the work to understand the cultures it represents, it falls back on clichés. But this approach is increasingly out of step with modern India. Audiences today are well-travelled, digitally connected, and quick to call out lazy portrayals.

If Bollywood wants to remain relevant in a pan-Indian and global market, it needs to rethink its playbook:

-

Authentic Casting: Cast actors who belong to the cultural background being portrayed.

-

Cultural Research: Writers and directors should invest in understanding regional nuances.

-

Moving Beyond Tropes: Stop equating South India with jasmine and idlis, Marathis with vada pav, and Biharis with violence.

-

Celebrate Diversity: Showcase characters as multidimensional, modern, and relatable, while still grounded in their cultural roots.

Cinema is not just escapist entertainment—it is also a mirror. And if the mirror is cracked with stereotypes, it reflects back a distorted image of India’s diversity.

Towards Respectful Representation

Bollywood has the power to unite, but it also has the power to divide. When it reduces communities to caricatures, it deepens divides—North vs South, urban vs rural, modern vs backward. Films like Param Sundari show how easy it is to slip back into old habits, while the rise of South Indian cinema shows that audiences crave authenticity.

It is time Hindi cinema asked itself: does it want to keep repeating tired clichés for cheap laughs and easy profits, or does it want to be remembered as a cinema that truly reflected India’s diversity? The answer will define not just the future of Bollywood, but also the cultural unity of India itself.

Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Vygr’s views.

With inputs from agencies

Image Source: Multiple agencies

© Copyright 2025. All Rights Reserved. Powered by Vygr Media.