Mahatma Gandhi once aptly said, “Earth provides enough to satisfy every man's needs, but not every man's greed.”

The timeless tradition of humans treating Earth like a free buffet of resources. With our knack for exhausting everything from oil to oxygen, coupled with the delightful consequences of carbon emissions, we're now reaping the rewards of our plundering ways. In India, from yesteryears to today, valiant social activists have been waging war on behalf of Mother Nature. Through their tireless efforts, they've been waving the flag for environmental and social justice, constantly reminding us all about the fragility of our precious Earth. It's almost as if we need a daily reminder not to trash the only home we've got.

What is an Environmental Movement?

An environmental movement refers to a social or political endeavor aimed at either conserving the environment or enhancing its condition. It is often interchangeably termed as the ‘green movement’ or ‘conservation movement’. These movements advocate for the sustainable stewardship of natural resources and frequently advocate for policy changes to safeguard the environment. Many of these movements focus on ecological preservation, public health, and human rights. They vary widely in organization, ranging from highly structured and institutionalized groups to more loosely organized grassroots initiatives. The geographical reach of environmental movements can span from local to nearly global scales.

-

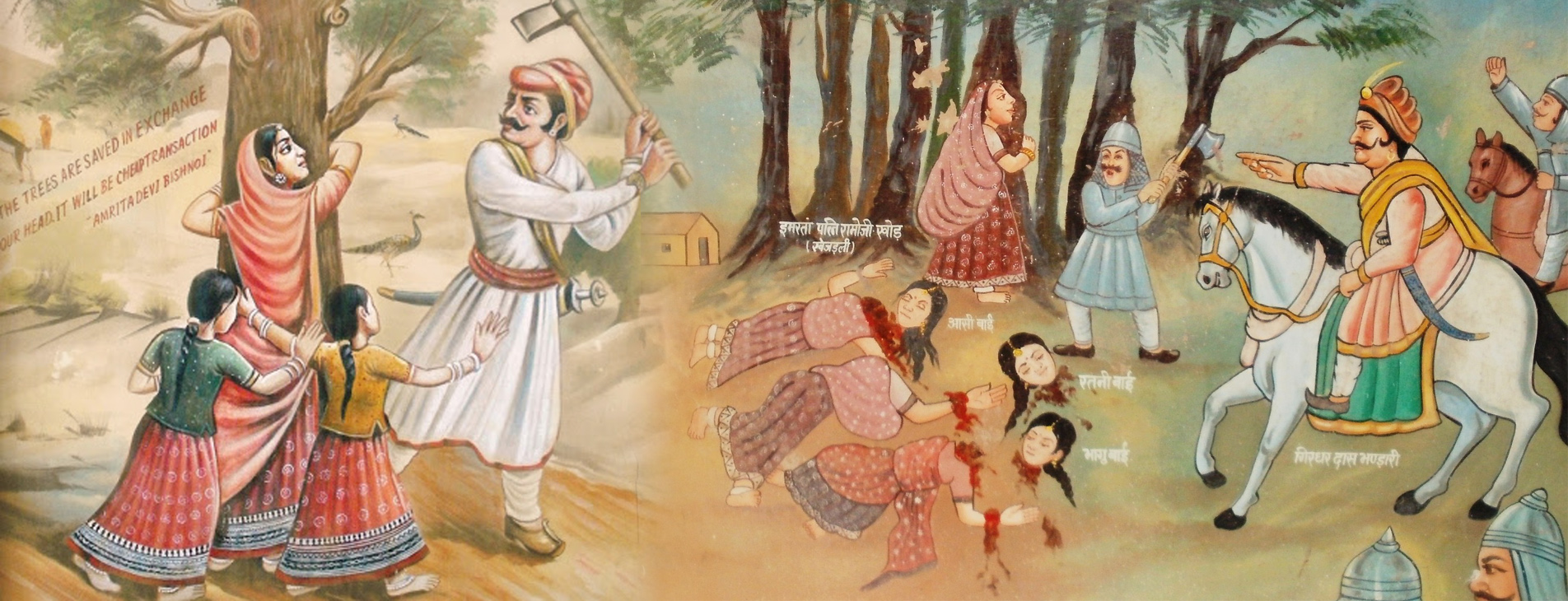

Year: 1700s

-

Location: Khejarli, Marwar region, Rajasthan state

-

Leaders: Amrita Devi and Bishnoi villagers

-

Objective: To protect sacred trees from being felled for a new palace

-

What was it all about: In the 1700s, the village of Khejarli in Rajasthan faced the threat of deforestation for the construction of a new palace. Amrita Devi, along with fellow Bishnoi villagers, stood against this exploitation of nature. Inspired by their faith's principles, which forbid harm to trees and animals, they embraced the trees slated for destruction. Their peaceful resistance resulted in the sacrifice of over 360 Bishnoi villagers. Upon learning of these events, the Maharaja intervened, apologizing to the community and halting the logging operations. As a tribute to their courage, he declared the Bishnoi state a protected area, ensuring the preservation of trees and wildlife. This historic legislation continues to safeguard nature in the region today.

-

Year: 1973

-

Location: Chamoli district and later Tehri-Garhwal district, Uttarakhand

-

Leaders: Sundarlal Bahuguna, Gaura Devi, Sudesha Devi, Bachni Devi, Chandi Prasad Bhatt, Govind Singh Rawat, Dhoom Singh Negi, Shamsher Singh Bisht, and Ghanasyam Raturi

-

Objective: Protection of trees on Himalayan slopes from forest contractors' axes

-

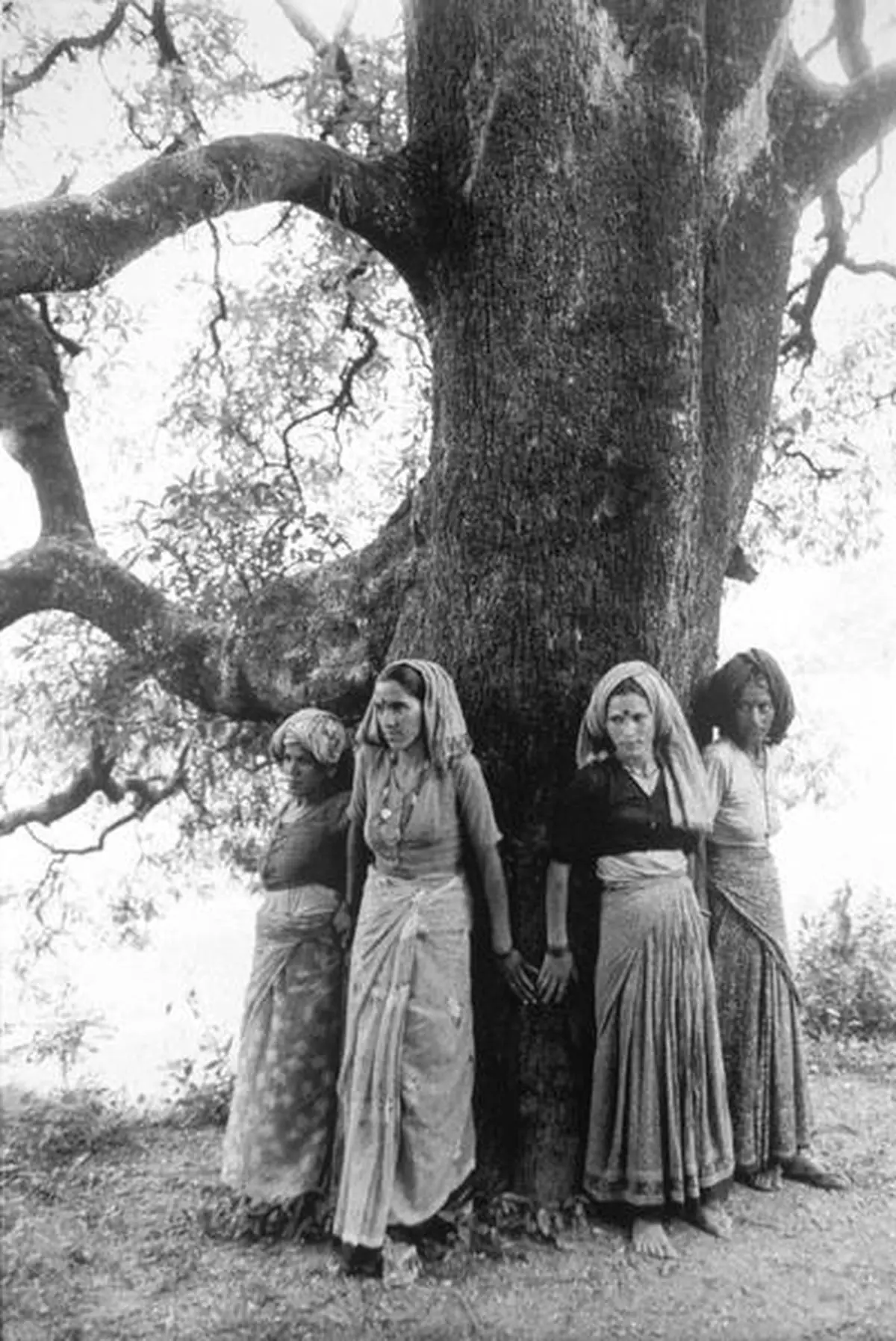

What was it all about: The Chipko Movement, spearheaded by Mr. Bahuguna, emerged as a response to the government's decision to allocate forest land to a sports goods company in Reni village, Uttarakhand. The women of Advani village, Tehri-Garhwal, symbolically safeguarded trees by tying sacred threads around their trunks and embracing them, thus initiating the 'hug the tree movement'. Central to their demands was the assertion that forest benefits, particularly fodder rights, should accrue to local communities. The movement gained traction in 1978 when women faced police repression, culminating in a favorable decision by the state Chief Minister Hemwati Nandan Bahuguna, marking a pivotal moment in the region's and global eco-development struggles.

-

Expansion: Originating in Reni, the Chipko Movement swiftly proliferated across Himalayan regions, as communities employed similar tactics to safeguard their forests. Its methods and message resonated globally, influencing environmental activism and policy formulation beyond national borders.

-

Government Response: The widespread support garnered by Chipko protesters catalyzed significant alterations in government forestry policies. In 1980, the Indian government enacted the Forest Conservation Act, curtailing commercial logging and emphasizing biodiversity preservation.

-

Cultural Impact: Beyond its environmental objectives, the Chipko Movement engendered heightened environmental awareness among Indians. It underscored the intrinsic link between local ecosystems and rural livelihoods, embedding environmental considerations into India's socio-political fabric.

-

Global Significance: The movement's triumph and novel non-violent protest strategies inspired environmental advocates worldwide. It became emblematic of grassroots activism's potency in shaping policy and safeguarding the environment, laying the groundwork for subsequent global conservation endeavors.

-

Legacy: Today, the Chipko Movement stands as a seminal event in environmental activism, revered for its advocacy of nature's inherent value and collective action's efficacy. Its enduring legacy is discernible in ongoing endeavors to harmonize development with environmental conservation and in communities' empowerment to assert their natural resource rights.

-

Year: 1978

-

Place: Silent Valley, Kerala, India

-

Leadership: The Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishad (KSSP) and poet-activist Sughathakumari spearheaded the Silent Valley protests.

-

Objective: Protecting Silent Valley, an unspoiled tropical rainforest in Kerala, from the proposed hydroelectric dam's detrimental impacts. The dam threatened to inundate vast forested areas, imperiling its unique biodiversity and disrupting ecological equilibrium.

-

What was it all about: The Kerala State Electricity Board (KSEB) proposed a hydroelectric dam on the Kunthipuzha River in 1973, sanctioned at a cost of approximately Rs 25 crores. However, opposition from NGOs and governmental reluctance led to the establishment of Silent Valley National Park in 1985. Subsequently, in November 1983, the dam project was shelved, and Silent Valley National Park was inaugurated in 1985. The grassroots campaign was ignited by local apprehensions regarding the dam's ecological repercussions, with figures like K. S. Sudhi and poet Sugathakumari at the forefront. A coalition comprising scientists, writers, and students supported the cause, with the KSSP playing a pivotal role in public awareness efforts.

-

Strategies: The movement adopted a multifaceted strategy encompassing legal recourse, scientific documentation of the valley's biodiversity, and public outreach. These endeavors were instrumental in building a compelling case against the dam, highlighting the irreplaceable loss of diverse flora and fauna.

-

Government Response: Intensifying public pressure prompted a thorough governmental reassessment. In 1983, the Prime Minister of India officially halted the hydroelectric project, marking a significant triumph for environmental conservation. This decision reflected the weight of public sentiment and acknowledgment of the valley's ecological significance.

-

Environmental Awareness: The Silent Valley Movement constituted a pivotal moment in India's environmental narrative, catalyzing awareness regarding the imperative to preserve biodiversity hotspots. It underscored the potential clash between developmental initiatives and environmental preservation, instigating a nationwide discourse on sustainable development paradigms.

-

Legal and Policy Implications: The movement's success instigated heightened scrutiny of projects impinging upon ecologically delicate regions. It played a pivotal role in shaping environmental statutes and regulations in India, notably contributing to the enactment of the Forest (Conservation) Act of 1980, which tightened controls on forest land diversion for non-forest purposes.

-

Legacy and Ongoing Influence: The conservation of Silent Valley as a national park stands as a testament to the efficacy of collective environmental activism. The movement has inspired successive cohorts of environmental advocates in India and worldwide, exemplifying how informed and persistent civic engagement can sway governmental policies and foster natural heritage preservation.

-

Global Recognition: The Silent Valley Movement enjoys international acclaim as a seminal event in the global environmental sphere, exemplifying how grassroots mobilization can safeguard biodiversity against the encroachments of industrial progress. It continues to serve as a cornerstone in environmental studies and policy curricula worldwide.

-

Year: 1980

-

Location: Western Ghats (Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu)

-

Leaders: Madhav Gadgil, Sunderlal Bahuguna, Prof. Kailash Chandra Malhotra, Kumar Kalanand Mani, Pandurang Hegde

-

Objective: The primary objective of the Save the Western Ghats Movement was to safeguard the immense biodiversity of the Western Ghats, recognized as one of the world's eight "hottest hotspots" of biological diversity. The movement aimed to halt detrimental development projects and foster sustainable practices to conserve the ecological balance of the region while supporting the livelihoods of local communities.

-

What was it all about: The Save the Western Ghats Movement (SWGM) emerged in 1986 as a response to the deterioration of the Western Ghats mountain range. Its inaugural demonstration in 1987 involved a months-long march along the range, advocating for sustainable approaches. Pioneering environmental activism in India, the SWGM served as a blueprint for subsequent campaigns. Led by figures like ecologist Madhav Gadgil, it brought together environmental groups, activists, and local residents from six states in the Western Ghats, organizing meetings, educational initiatives, and awareness campaigns to highlight the region's plight nationally.

-

Strategies and Activities: The movement employed diverse strategies, including scientific research to catalog the area's biodiversity, public awareness drives, legal actions, and lobbying for policy reform. A pivotal initiative was the establishment of the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel (WGEEP), also known as the Gadgil Commission, entrusted with evaluating the region's ecological health and proposing conservation measures.

-

Impact on Conservation Policies: The movement's endeavors catalyzed significant policy transformations. It led to stricter environmental regulations for industries and development ventures in the region, the adoption of more stringent conservation measures, and the integration of sustainable development principles into planning frameworks. Crucially, its advocacy contributed to the recognition of several Western Ghats areas as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, acknowledging their exceptional global significance.

-

Enhancing Environmental Awareness: Beyond policy changes, the Save the Western Ghats Movement heightened public awareness and comprehension of environmental issues in India. It underscored the inseparable link between biodiversity conservation and sustainable development, shaping public discourse and educational initiatives on environmental stewardship.

-

Legacy and Continuing Initiatives: The movement's legacy endures, inspiring ongoing conservation efforts and environmental activism both within and beyond the Western Ghats. It stands as a testament to the efficacy of grassroots mobilization, backed by scientific research and advocacy, in driving substantive environmental protection and policy reform.

-

Challenges and Disputes: Despite its achievements, the movement encountered challenges, particularly in reconciling conservation objectives with economic development imperatives and addressing the grievances of local communities impacted by conservation policies. The recommendations of the Gadgil Commission, for instance, sparked debates over land use regulation and economic growth, underscoring the complexities inherent in environmental governance.

-

Year: 1982

-

Location: Singhbhum district, Bihar

-

Leaders: Tribal communities of Singhbhum

-

Objective: Opposing the government's plan to substitute indigenous sal forests with teak.

-

What was it all about: The indigenous tribes residing in Bihar's Singhbhum district initiated a protest against the government's proposal to replace the native sal forests with teak, a decision viewed by many as driven by political opportunism and greed. This movement gained momentum, extending its reach to the neighboring states of Jharkhand and Orissa.

-

Year: 1983

-

Location: Uttara Kannada and Shimoga Districts, Karnataka State

-

Leaders: The strength of the Appiko movement stemmed from its lack of reliance on any single personality or formal institutionalization. Instead, it found guidance through facilitators like Pandurang Hegde, who spearheaded its inception in 1983.

-

Objective: To combat deforestation, commercial exploitation of natural forests, and the degradation of traditional livelihoods.

-

What was it all about: The Appiko movement, locally known as "Appiko Chaluvali," emerged as a regional counterpart to the Chipko movement. Communities rallied around trees marked for felling by forest department contractors, employing tactics such as foot marches, slide shows, folk dances, and street plays to raise awareness. Additionally, the movement aimed to reclaim denuded lands through afforestation efforts and advocated for the rational utilization of the ecosystem, promoting alternative energy resources to alleviate pressure on forests. While initially successful, the movement has since halted, marking the current status of the project as inactive.

-

Year: 1985

-

Location: The Narmada River, traversing Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra.

-

Leadership: Medha Patkar, Baba Amte, indigenous tribes, farmers, environmentalists, and human rights activists.

-

Objective: The Narmada Bachao Andolan sought to halt the construction of large dams on the Narmada River due to concerns over massive displacement of people, particularly indigenous tribes and rural communities, and ecological disruption.

-

What was it all about: Originating as opposition to the Sardar Sarovar Dam (NAB), the movement initially focused on rehabilitation and resettlement for displaced individuals. Over time, it evolved to emphasize environmental preservation and advocated for reducing the dam's height from 130m to 88m. Despite the World Bank's withdrawal from the project, the Supreme Court approved a 90m height, exceeding the movement's demands. Funded by state governments and market borrowings, the project is slated for completion by 2025. Though not entirely successful, the NBA sparked anti-big dam sentiments in India and globally, challenging prevailing development paradigms. Medha Patkar and Baba Amte spearheaded grassroots activism, mobilizing communities, raising issues on national and international platforms, and contesting dam projects through legal and public avenues.

-

Expansion and Support: The NBA expanded into a coalition involving activists, academics, environmentalists, and human rights organizations, receiving backing from various sectors, including prominent figures like Arundhati Roy and groups like Friends of the Earth. Non-violent protests, such as hunger strikes, marches, and legal battles, underscored the movement's commitment to social justice and environmental sustainability.

-

International Recognition: The NBA garnered global attention to the plight of Narmada River communities and the environmental risks of large dam projects, challenging development models prioritizing infrastructure over ecological and social well-being. Its international visibility pressured the Indian government and international funding agencies, notably the World Bank, leading to the bank's withdrawal of funding for the dam project.

-

Impact on Policies and Practices: The movement spurred debates on India's dam policies, displacement, and rehabilitation practices, influencing the development of more comprehensive rehabilitation policies, though their implementation remains a challenge. It also fostered critical discourse on sustainable development, environmental justice, and indigenous peoples' rights in development projects.

-

Legacy: The Narmada Bachao Andolan stands as a pivotal movement in India's environmental and social activism history, inspiring numerous grassroots movements advocating for displaced communities' rights and environmental conservation. It persists in advocating for justice for those impacted by Narmada dam projects and promoting ecologically sustainable and socially equitable development models.

-

Ongoing Challenges: Despite its achievements, the movement reflects the ongoing struggle between development aspirations and ecological preservation. Controversies surrounding the construction of the Sardar Sarovar Dam and other Narmada dams persist, with advocates and affected residents pushing for fair and environmentally friendly solutions.

-

Year: 1990’s

-

Location: Bhagirathi River near Tehri in Uttarakhand.

-

Leaders: Sundarlal Bahuguna

-

Objective: The protest aimed to address the displacement of town inhabitants and the ecological ramifications of an unstable ecosystem. It sought to highlight the adverse environmental consequences and the societal impact of relocating thousands due to the construction of the Tehri Dam, one of the world's tallest. The objective was to prompt a reconsideration of the project in favor of sustainable and less harmful alternatives.

-

What was it all about: The Tehri Dam garnered national attention in the 1980s and 1990s, facing notable objections such as the seismic vulnerability of the area and the submergence of forests, including Tehri town. Despite backing from leaders like Sunderlal Bahuguna, the movement struggled to gain widespread support domestically and internationally. Bahuguna, renowned for his involvement in the Chipko Movement, led the protest, employing hunger strikes and rallying both national and international backing for renewable energy solutions and the rights of those affected by the dam's construction.

-

Impact and Public Discourse: Though the Tehri Dam construction proceeded, the protest sparked a significant debate on the viability of large dam projects in India. It raised questions about environmental evaluations, the resettlement of displaced communities, and the enduring ecological effects of such endeavors.

-

Policy Influence: The Tehri Dam Protest prompted a crucial reassessment of dam policies in India, stressing the necessity for thorough environmental assessments and improved rehabilitation strategies. It emphasized exploring alternative, sustainable energy sources with lesser impacts on ecosystems and communities.

-

Legacy: The Tehri Dam Protest remains a notable episode in India's environmental activism annals, highlighting ongoing challenges and discussions regarding extensive infrastructure projects, environmental sustainability, and the rights of displaced populations. It continues to inspire activism and awareness concerning the intricate balance between development and conservation efforts.

-

Year: 2014

-

Location: Aarey Milk Colony, Mumbai, Maharashtra

-

Leaders: Amrita Bhattacharjee, Aditya Thackarey, Nandkumar Pawar, Zoru Bathena, Tabrez Ali Sayed, Siddharth A

-

Objective: The movement aimed to safeguard the Aarey Milk Colony, a vital green zone in Mumbai, from the proposed construction of a metro car shed, which posed a threat to over 2,000 trees. Its goal was to emphasize the importance of preserving urban forests for biodiversity, climate regulation, and the well-being of city residents.

-

What was it all about: The Save Aarey movement emerged in 2014 as a grassroots response to prevent tree felling in Aarey for the Mumbai metro's Line 3 car shed. Through protests and legal avenues including petitions to the National Green Tribunal, Bombay High Court, and Supreme Court, activists attempted to halt the project and designate Aarey as a forest. Despite initial setbacks, the movement gained traction, particularly after the Supreme Court intervened in June 2023, suspending deforestation in Aarey and directing the BMC to cease tree cutting for the shed construction.

-

Strategies and Actions: Activists employed a diverse strategy combining peaceful demonstrations, symbolic tree-hugging reminiscent of the Chipko Movement, and legal challenges. Media outreach and support from notable figures bolstered their cause.

-

Government Response and Outcome: In a significant victory in 2019, the Maharashtra government announced the relocation of the metro car shed, thereby preserving Aarey's trees and forest area.

-

Significance and Impact: The Save Aarey Movement showcased the efficacy of grassroots activism in urban environmental conservation, highlighting the importance of public engagement in influencing governmental decisions. It emphasized the vital role of urban green spaces in maintaining ecological equilibrium and providing recreational areas for urban populations.

-

Legacy and Ongoing Initiatives: The success of the movement has inspired similar endeavors nationwide, advocating for the protection of urban natural resources and promoting sustainable urban planning that integrates green spaces into development projects. It also emphasized the importance of civic engagement in environmental governance, emphasizing community involvement in shaping policies affecting their surroundings.

-

Broader Implications: The movement's success emphasized the indispensable role of urban forests in maintaining a city's environmental balance. It sparked discussions on environmental equity, ensuring communities have access to green spaces, and the necessity of environmental considerations in urban development planning.

-

Yettinahole Diversion Project Protests: In Karnataka, there have been protests against the Yettinahole River diversion project, which involves the felling of trees in the Western Ghats to divert water to other regions. Environmentalists argue that this would harm the fragile ecosystem of the Western Ghats.

-

Save Delhi Trees Campaign (Ongoing): In response to extensive tree felling for development projects and urbanization in Delhi, several citizen-led campaigns have emerged to protect trees and green spaces in the city.

-

Save Mollem Movement (2020): In Goa, this movement opposed three infrastructure projects that threatened the Mollem National Park and Bhagwan Mahavir Wildlife Sanctuary.

-

Save Aravali Movement (Ongoing): Various initiatives and protests aim to protect the Aravalli Range, a significant forest area in Rajasthan, Haryana, and Delhi, from encroachment and illegal mining.

-

Kudimaramathu Movement (2019): Initiated in Tamil Nadu, it's a community-based movement focused on restoring water bodies, including the planting of trees along water sources.

-

Save Banni Movement (2021): This movement aimed to conserve the Banni Grasslands Reserve in Gujarat, which is one of the largest tropical grasslands in Asia and home to diverse flora and fauna.

-

Save Belapur Hills (Ongoing): In an incident reminiscent of the Chipko movement, residents and nature enthusiasts in Navi Mumbai joined hands on Sunday to quietly protest against the destruction of Belapur Hill. The residents, which included many women as well, expressed their concerns about rapid encroachments, illegal temple construction, and tree cutting.

As we reflect on the past, let us also look to the future with optimism and resolve. Let us draw inspiration from the courage of those who came before us and embrace our role as stewards of the Earth. For in our hands lies the power to shape a brighter, more sustainable tomorrow.

Together, let us heed the call to action, for the sake of our planet, our communities, and the countless species that call Earth home. Let us stand united in our commitment to protect and preserve, knowing that our collective efforts can indeed make a difference.

So let us march forward, hand in hand, towards a future where harmony between humanity and nature is not just a dream, but a reality we create together.

In the words of Margaret Mead, "Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it's the only thing that ever has."

Image Source: Multiple agencies

With inputs from agencies

© Copyright 2024. All Rights Reserved Powered by Vygr Media.