“How many more daughters must burn before India decides that dowry is not just illegal, but intolerable?”

On the night of August 21, in a modest house in Greater Noida, 28-year-old Nikki Bhati was beaten unconscious, doused with a flammable liquid, and set on fire by the man she had married in 2016 her husband, Vipin. She stumbled down the staircase engulfed in flames, her body a living torch, as her six-year-old son watched and screamed. Hours later, she died.

The videos of her last moments filmed by her sister Kanchan, who herself had married into the same family, are among the most harrowing India has ever seen. In one clip, Nikki sits helplessly as her husband towers over her. In another, flames consume her as she runs, trying desperately to escape. And in the most gut-wrenching evidence of all, Nikki’s little boy is heard telling relatives: “Papa killed Mummy by burning her with a lighter.”

Her crime? Not bringing enough dowry.

Despite already giving a Scorpio SUV, a Royal Enfield, gold, and cash at marriage, Nikki’s family was allegedly harassed for an additional ₹36 lakh. When she expressed a wish to restart her beauty parlour and post on Instagram, Vipin snapped. “In our family, this is not allowed,” he told her, before setting her on fire.

Nikki’s story is not just about one woman, one family, one crime. It is the mirror India refuses to look into, a mirror that shows how, in 2025, in the world’s largest democracy, women are still dying for dowry.

Alarming Numbers from NCRB

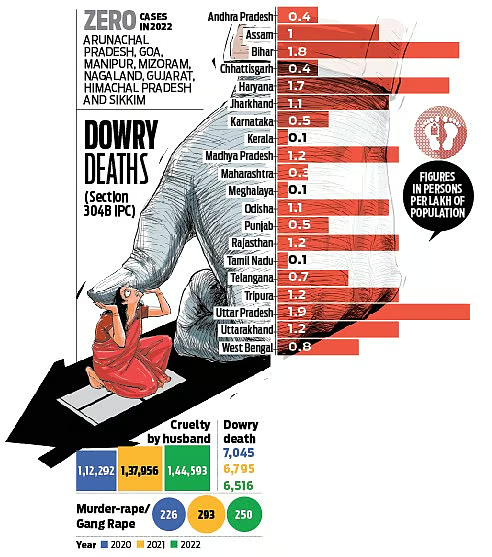

The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data reveals a devastating reality: in 2022 alone, 6,516 women lost their lives due to dowry-related violence. Between 2017 and 2022, India witnessed 35,493 dowry killings, averaging almost 20 deaths every day, making dowry deaths one of the most persistent forms of gender-based violence in the country.

Despite being prohibited under law since the Dowry Prohibition Act of 1961, the practice continues. Families of brides are still expected to provide cash, jewellery, clothes, and other valuables to the groom’s side. Failure to meet these demands frequently results in harassment, torture, and in many cases, death, often by burning.

Comparatively, in 2020, police registered 1,12,292 cruelty cases, showing a sharp rise in just two years. Meanwhile, dowry deaths remained consistently between 6,500–7,000 annually, alongside 1,700 suicides linked to dowry harassment, and murder-rape incidents never crossed 300 cases per year. Experts believe the real numbers are much higher.

Although there has been a marginal decrease from 7,045 deaths in 2020, the numbers remain unacceptably high.

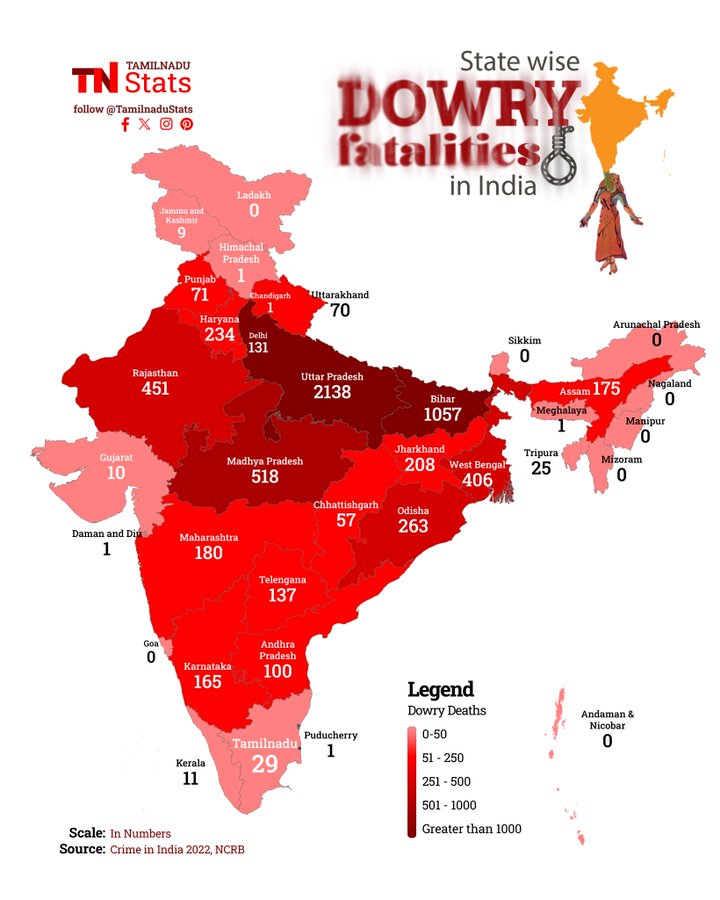

State-Wise Breakdown of Dowry Deaths (2022)

-

Uttar Pradesh: 2,142 deaths

-

Bihar: 1,057 deaths

-

Madhya Pradesh: 520 deaths

-

Rajasthan: 451 deaths

-

West Bengal: 427 deaths

-

Odisha: 263 deaths

-

Haryana: 234 deaths

-

Jharkhand: 214 deaths

-

Assam: 195 deaths

-

Kerala: 12 deaths

-

Tamil Nadu: 29 deaths

When adjusted for population, the statistics remain alarming:

-

UP: 1.9 dowry deaths per lakh women

-

Bihar: 1.8

-

Haryana: 1.7

-

MP: 1.2

Beyond Deaths: The Cruelty Within Marriages

While dowry deaths are the most extreme manifestation, they represent only a fraction of the violence women face in marriages. In 2022, the NCRB recorded 1,44,593 cases under Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code cases related to cruelty by husbands or in-laws.

To contextualise:

-

Dowry deaths (2022): 6,516

-

Cases of cruelty under Section 498A (2022): 1,44,593 (over 20 times higher)

-

Murder-rape or gang-rape cases (2022): 250

The figures reveal that for every dowry death, countless others are enduring prolonged cruelty.

This steady rate of dowry deaths, combined with the surge in cruelty cases, underlines a worsening problem despite existing legal measures such as Section 304B of the IPC (dowry death provision) and the Dowry Prohibition Act. Behind each case lies the same grim pattern bride’s family gives, in-laws demand more, cruelty escalates, and one day, a young woman is either driven to suicide or murdered. That means that by the time you finish reading this article, another woman, somewhere in India, may already have been set on fire.

A Pattern of Abuse, a Predictable End

Nikki’s case sparked outrage, but it is hardly unique. Each day, 20 women in India die because of dowry harassment, burned, hanged, poisoned, or driven to suicide.

-

The Jodhpur Tragedy: On August 22, in a village near Delhi, Sanju Bishnoi, a school teacher in Jodhpur, Rajasthan, was so tormented by dowry demands that she set herself and her three-year-old daughter on fire. She seated her child on her lap, poured inflammable liquid, and ignited it. The child died instantly, and Sanju succumbed to her injuries the following day. “I can’t take this anymore,” she said.

-

The Jaipur Case: In June 2022, the three Meena sisters, Anju, Nitu, and Anita, who were married to three brothers of the same family in Rajasthan's Jaipur district, jumped into a river with their children after leaving messages about relentless dowry abuse. Their last WhatsApp statuses read like epitaphs: "It's better to die once and for all than die every day…We don't want to die, but our in-laws harass us. We don't wish to die, but death is better than their abuse. Our in-laws are the reason behind our deaths. We are dying together because it's better than dying every day." All three sisters were found dead near their marital home, along with Kalu's four-year-old son and infant child. Both Kamlesh and Mamta were pregnant.

-

The Khargone Case (Madhya Pradesh): A 23-year-old newlywed woman, married for just six months, was admitted to the hospital with severe burn injuries. She alleged that her husband, Dilip Pipaliya, heated a knife on a gas stove and branded her across her body in connection with dowry demands. Her brother rescued her after receiving information and rushed her to the hospital. Speaking from her hospital bed, the survivor accused her husband of repeatedly beating her and demanding dowry. Her father confirmed that his son-in-law often assaulted her for money and material demands. Police have registered a case.

-

The Hyderabad Murder (Telangana): On August 23, a horrific case unfolded in Hyderabad. Samala Mahender Reddy (27), a cab driver, murdered his five-months-pregnant wife, B. Swathi dismembered her body and disposed of the parts in the Musi River. The couple, from different castes, had a love marriage in January 2024 against parental wishes. However, Mahender reportedly harassed Swathi for dowry. Earlier, in April 2024, she had filed a dowry harassment complaint with Vikarabad police under Section 498A IPC and Section 4 of the Dowry Prohibition Act.

-

The Kothagudem Case (Telangana): On the same day, August 23, a 33-year-old woman, Lakshmi Prasanna, was found dead under suspicious circumstances in Kothagudem district. Married to Poola Naresh Babu since 2015, her family alleged she was subjected to starvation, beatings, and two years of house arrest. At the time of marriage, her parents provided two acres of mango orchards, half an acre of farmland, Rs 10 lakh in cash, and gold ornaments worth Rs 10 lakh. Despite this, she was allegedly isolated, denied phone access, and kept under constant surveillance. She was declared dead at Rajamahendravaram Government Hospital.

The Laws on Paper

India outlawed dowry more than 60 years ago through the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961. The law criminalises giving, taking, or even demanding dowry. Under Section 3, offenders can face up to 5 years in prison and hefty fines. Section 4 criminalises indirect demands as well.

It is not that India lacks laws. In fact, on paper, our legal arsenal looks strong:

-

The Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961: criminalises the giving, taking, or demanding of dowry.

-

Section 498A, IPC (now Section 85, BNS): criminalises cruelty by husband or in-laws.

-

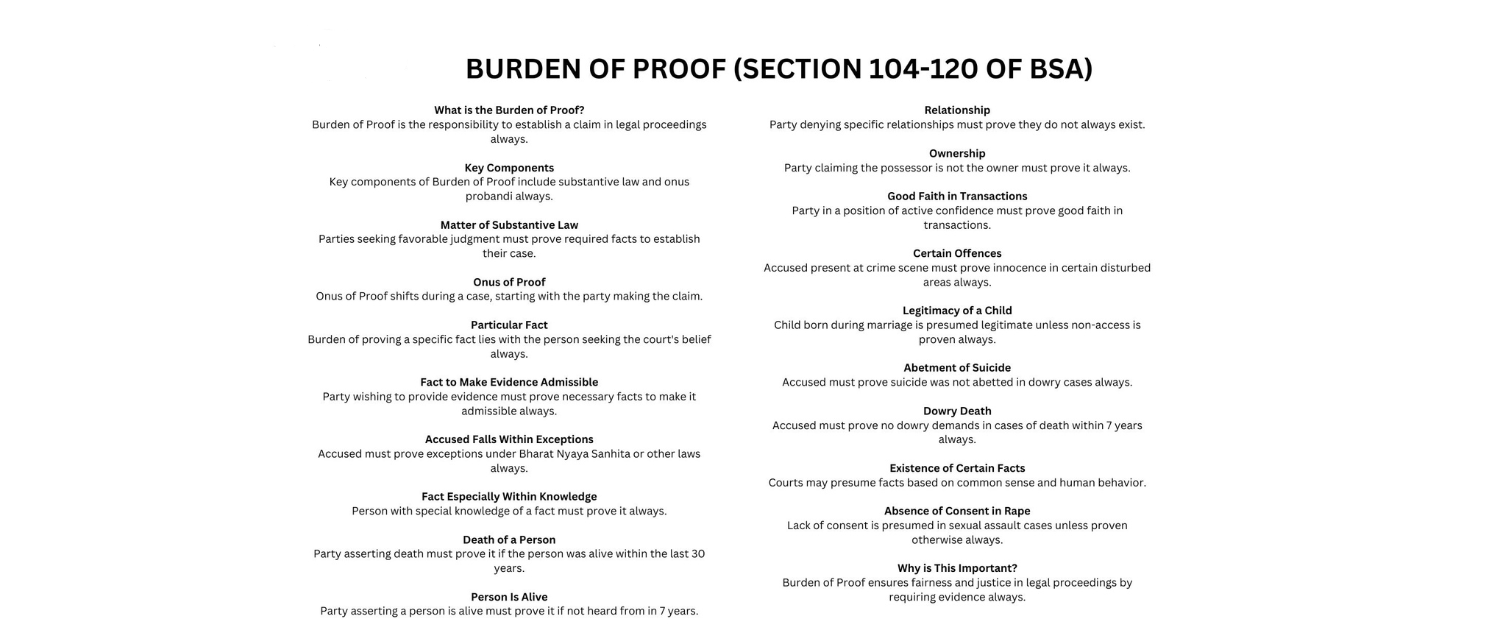

Section 304B, IPC (now Section 80, BNS): defines dowry death if a woman dies within seven years of marriage in suspicious circumstances, the husband and in-laws are presumed guilty.

-

Section 306, IPC: abetment of suicide due to harassment.

-

Section 113B, Evidence Act (now Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam): shifts the burden of proof to the accused once dowry harassment is established.

-

Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005: safeguards women from physical and emotional abuse.

On paper, these laws are airtight. In practice, they leak like a sieve.

Nikki herself endured nine years of documented abuse. Her family provided luxury vehicles and valuables at marriage. When demands for ₹36 lakh came, they still tried to appease. Each time she returned beaten, her parents sent her back, praying things would improve. The Bhati family’s abuse was no secret. Yet it took her death, her sister’s video evidence, and her son’s testimony for the police to act.

And here lies the heart of the failure: laws without enforcement are not protection, they are decoration.

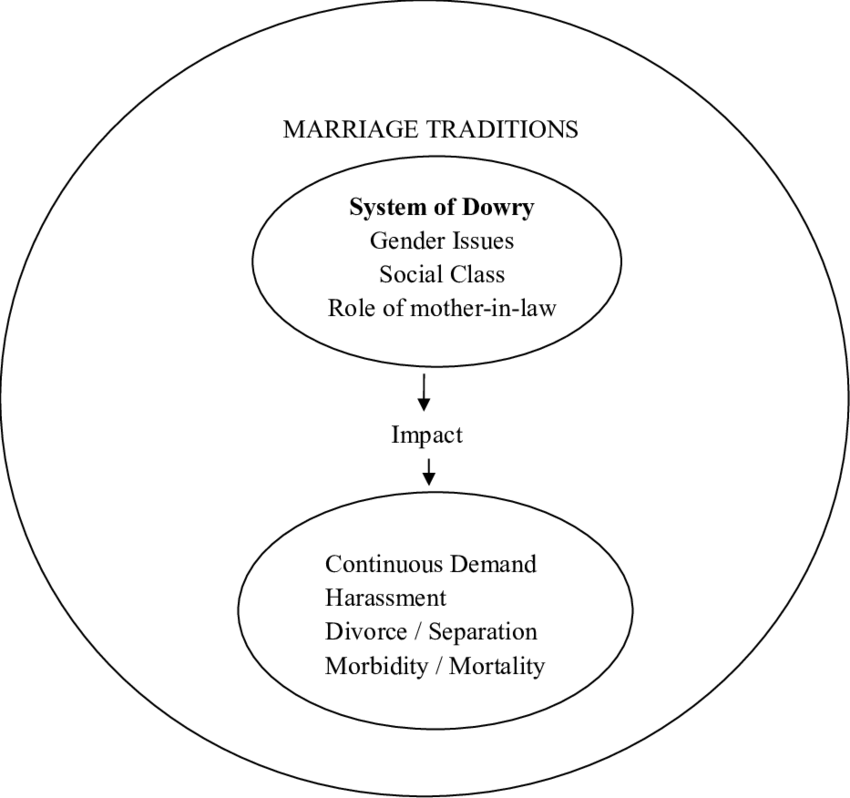

Why Dowry Refuses to Die

Dowry is not just an “evil practice.” It is a deeply entrenched social contract that thrives on patriarchy, greed, and silence. If laws exist, why does dowry continue to claim lives? The reasons are complex and deeply embedded in society:

- Dowry as a Tool of Patriarchal Control: Marriages are treated as financial negotiations, where the groom’s family believes they are “selling” a son and must be compensated. The bride is seen not as a partner, but as a "burden" needing “payment.” Dowry has morphed into a symbol of patriarchal dominance, reinforcing the notion that a girl is a liability, and her parents must meet so-called obligations. A landmark study by Jeffrey Weaver (University of Southern California) and Gaurav Chiplunkar (University of Virginia), which analysed over 74,000 marriages between 1930 and 1999, revealed that 90% involved dowry. The cumulative payments between 1950 and 1999 alone were estimated at a staggering quarter of a trillion dollars. Male entitlement, coupled with the cultural conditioning that instructs women to “endure and stay silent,” perpetuates the system.

-

Wealth and Status: Dowry is seen as a transaction that “elevates” the groom’s family’s financial standing.

-

Education and Marriage Market: Educated, employed men often “cost” more in dowry negotiations.

-

Gender Bias: Girls are still treated as economic burdens, while boys are “assets.”

-

Economic Dependency: With female labour force participation in India among the lowest in the world (just 19% in 2020), women often lack the financial independence to walk away. Even though women increasingly hold high-paying jobs, they are still perceived as dependents, with dowry often serving as a way to satisfy male ego. When such control feels threatened, it frequently escalates to abuse and violence, often carried out without fear of consequences.

-

Social Collusion: Neighbours, relatives, even entire villages often “adjust” and normalise abuse as “ghar ke maamle” (household matters).

-

Parental Fear of Shame and Silence: Parents fear stigma if they don’t provide lavish gifts. A woman leaving her marital home is seen as a disgrace. Parents frequently persuade daughters to endure violence rather than return home.

The World Bank studied rural India between 1960–2008 and found that dowry was paid in 95% of marriages. Six decades after being outlawed, dowry is still a normalised gift-wrapped in the language of “gifts” and “tradition.” As a result, dowry is not just a family issue. It is a society-wide conspiracy of silence.

The Misuse Debate: A Convenient Distraction

Critics often argue that dowry laws are “misused.” Courts have even used phrases like “legal terrorism” to describe false cases under Section 498A.

The suicide of Atul Subhash, who left a note blaming his wife’s family for falsely accusing him of dowry harassment, is often cited as proof. Indeed, misuse exists; no law is immune. But focusing only on misuse risks trivialises the thousands of genuine victims.

The Supreme Court itself has said: “Misuse of a law does not make the law itself bad.” If anything, misuse highlights poor investigation and lack of checks problems that should be fixed with better policing and accountability, not by weakening protections.

Because for every false case, hundreds of Nikkis never live to tell their truth.

Lawyer Seema Kushwaha on Legal Loopholes and Low Conviction Rates

Supreme Court advocate Seema Kushwaha highlighted the reasons behind the low conviction rates. According to her:

“Dowry demands have evolved over time, with the groom's families often claiming that the items given were mere ‘gifts, not demands,’ and using this as a legal defence to dismiss allegations. This common tactic significantly weakens the woman's case in court”

She further noted that public narratives about the alleged misuse of Section 498A undermine genuine victims, creating bias against women seeking justice. Introduced in 1983 after a spate of dowry deaths, Section 498A was intended as a strong deterrent but often faces dilution in practice.

Kushwaha also questioned why everyday acts of abuse often go unpunished:

“Why is it that a husband slapping his wife or in-laws blaming her family for trivial matters soon after marriage does not immediately result in an FIR?”

“Courts often interpret cruelty based on societal norms rather than strictly following codified law. They require medical reports or visible bruises to confirm cruelty, which unfairly disadvantages victims of mental and emotional abuse that leave no physical marks,” she said.

The Burden of Proof and the Justice Gap

One major hurdle in dowry death cases is evidence. Abuse usually happens behind closed doors. Victims rarely leave proof. That is why Section 113B of the Evidence Act (now Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam) was introduced, shifting the burden of proof to the husband and in-laws when dowry harassment is established.

But enforcement is weak. Police often dismiss early complaints as “domestic quarrels.” Families stay silent to avoid shame. By the time the law steps in, another woman is dead.

The uncomfortable truth: dowry cases rarely end in convictions. Families turn hostile, evidence is tampered with, and witnesses are silenced. Judges hesitate to convict in-laws without “proof beyond a reasonable doubt,” ignoring the very reason Section 113B was created, because such crimes rarely happen in the open.

Who is Responsible?

-

Bride’s Parents: For years, Nikki’s parents endured humiliation in silence. They feared social stigma and placed the sanctity of their daughter’s “marital home” above her safety. In doing so, they lost her forever. This silence must end. Protecting daughters must matter more than protecting family honour. Parents should not simply “marry and forget”; they must remain vigilant, stay emotionally connected, and ensure their daughter always knows she has a safe place to return to without fear of judgment or blame.

As Seema Kushwaha, a SC lawyer, stressed:

“We often portray parents of victims solely as victims themselves, but sometimes, they also enable these situations. Every dowry victim girl must have expressed distress multiple times. Still, the parents sent her back, fearing society's judgment, choosing image over her safety. And we all know it's never the first time the girl gets beaten.”

-

The Bride: It is cruel and unfair to demand endless resilience from victims. Still, awareness is a vital shield. Economic independence, education, and the refusal to normalise abuse are weapons no law can replace. Independence, however, is not just financial; it must be emotional and mental as well. Women should be empowered to resist emotional blackmail, coercion, and manipulation, so they never feel trapped in abusive relationships.

-

Society: Neighbours who hear screams, relatives who witness bruises, friends who notice desperate hints in WhatsApp statuses, all are complicit if they remain silent. Justice demands collective courage. Instead of criticising the bride or blaming her parents, society must unite to support them and hold abusive families accountable. The fight against dowry violence requires active intervention, not whispered sympathy. Because today, it may be someone else’s daughter tomorrow, it could be yours.

-

Law and State: Police must treat dowry complaints as red alerts, not dismiss them as “family disputes.” Every complaint should be recorded, investigated, and acted upon urgently. Courts must deliver justice swiftly, with trials prioritised to prevent endless delays that only deepen trauma. Lawmakers must enforce harsher penalties for habitual offenders while ensuring safeguards against malicious or false cases. False filings should be penalised, but never at the cost of silencing real victims. Justice must be certain, swift, and strong enough to deter future cruelty.

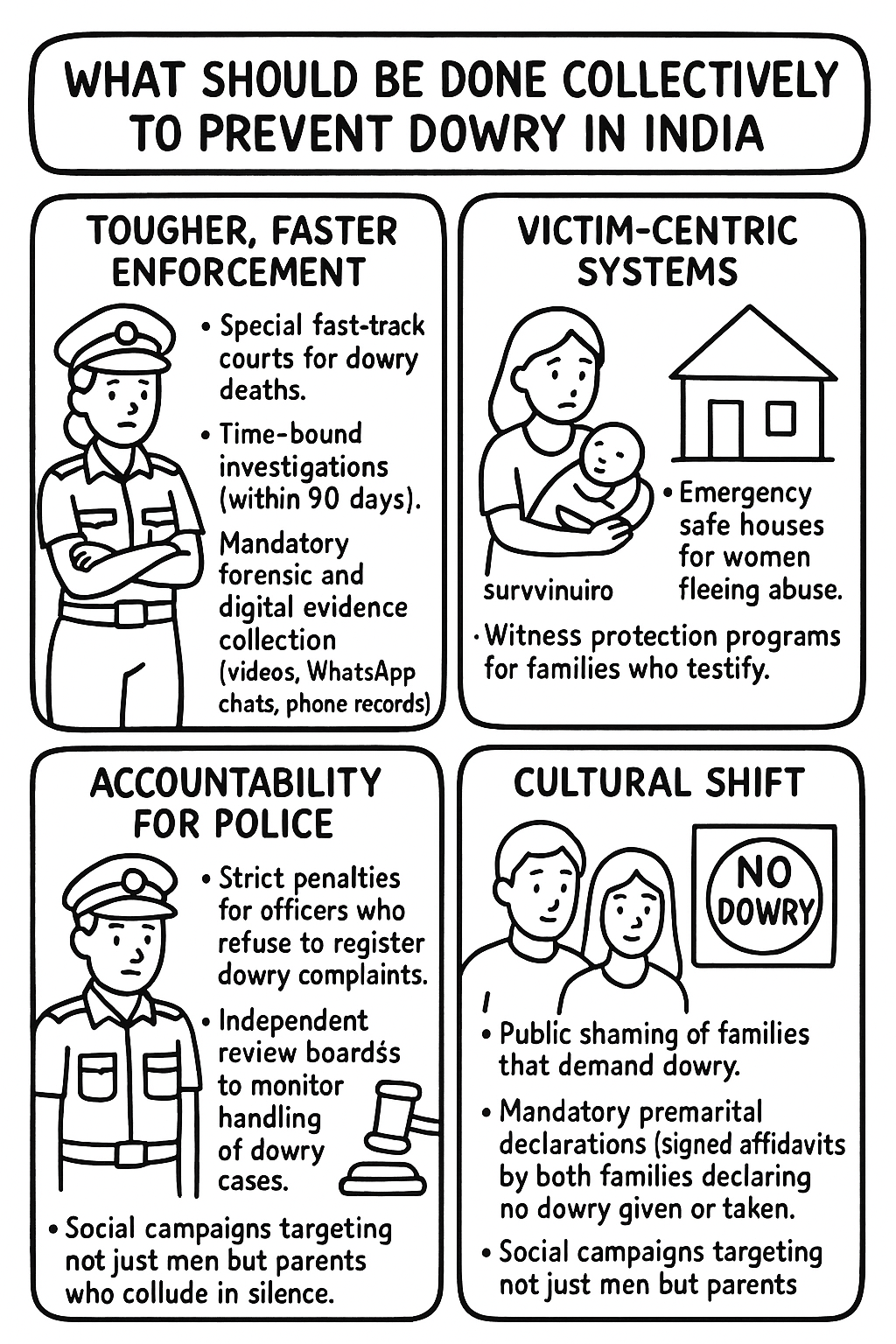

What Must Change

If Nikki’s death is not to be in vain, India must confront dowry with more than hashtags and outrage cycles.

-

Tougher, Faster Enforcement

-

Special fast-track courts for dowry deaths.

-

Time-bound investigations (within 90 days).

-

Mandatory forensic and digital evidence collection (videos, WhatsApp chats, phone records).

-

-

Victim-Centric Systems

-

Emergency safe houses for women fleeing abuse.

-

Financial assistance and skill training for survivors to rebuild their lives.

-

Witness protection programs for families who testify.

-

-

Accountability for Police

-

Strict penalties for officers who refuse to register dowry complaints.

-

Independent review boards to monitor handling of dowry cases.

-

-

Cultural Shift

-

Public shaming of families that demand dowry.

-

Mandatory premarital declarations (signed affidavits by both families declaring no dowry given or taken).

-

Social campaigns targeting not just men but parents who collude in silence.

-

-

Balanced Safeguards Against Misuse

-

Penalise demonstrably false cases but only after trial, not at the FIR stage.

-

Improve investigation quality to separate genuine cases from malicious ones.

-

A Call to Conscience

At its core, dowry is not about money. It is about power, control, and the disposability of women’s lives. Nikki Bhati’s death is not just another case file. It is a mirror to our collective failure. A society where daughters are still priced, bought, and burned cannot call itself modern. We can no longer shrug and say, “This is how it is.” It doesn’t have to be.

The law is there. What is missing is the willpower of families to say no, of police to act fast, of society to raise its voice. Dowry will not die by legislation alone. It will die when giving or demanding it becomes a matter of shame, not pride.

As Nikki’s father cried, “They are butchers. They killed my innocent daughter for money. I want an encounter.” His rage is not just his. It belongs to every parent, every sister, every brother who fears their loved one could be next.

Her death should haunt us. Every flame that consumed her body should scorch our conscience.

Because until we stop treating daughters as liabilities, until parents stop negotiating marriages like business deals, until neighbours stop saying “adjust kar lo”, until laws stop being ink on paper, more Nikkis will burn.

And when they do, the real killers will not just be their husbands or in-laws. The real killers will be us, a society that watched and stayed silent.

Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect Vygr’s views.

With inputs from agencies

Image Source: Multiple agencies

© Copyright 2025. All Rights Reserved. Powered by Vygr Media.