The Square Kilometre Array (SKA), the world’s largest telescope, initially set to expand into eight African countries, has revised its expansion timeline. The SKA, which is based in Australia and South Africa, will delay its growth beyond these countries due to funding constraints.

Project Evolution

At the International Astronomical Union’s general assembly in Cape Town this August, SKA director-general Philip Diamond announced that the observatory’s plans had evolved. The project’s large-scale expansion into other African countries, originally scheduled after the site selections in 2012, will no longer happen as planned.

Diamond explained to Nature, “Moving from the current funding to a massive monolithic phase is probably impractical at this stage. We’re now looking at a more phased, continuous deployment.”

Pontsho Maruping, managing director of the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory (SARAO), emphasized that while the timing of the expansion may change, the scientific goals remain intact. "As soon as more funding is committed, additional infrastructure will be deployed, including remote stations," she said.

Concerns were raised about the potential loss of research capacity in the African nations originally slated for the SKA expansion. The African Astronomical Society and Ghana Space Science and Technology Institute were contacted, but both referred queries to SARAO and the SKA Observatory (SKAO) headquarters in the UK.

Diamond noted that whether the telescope will ever achieve the planned "square kilometre" of collecting area is unclear, stating, “It’s for future leaders to take us there.”

How SKA Works and Its Current Funding

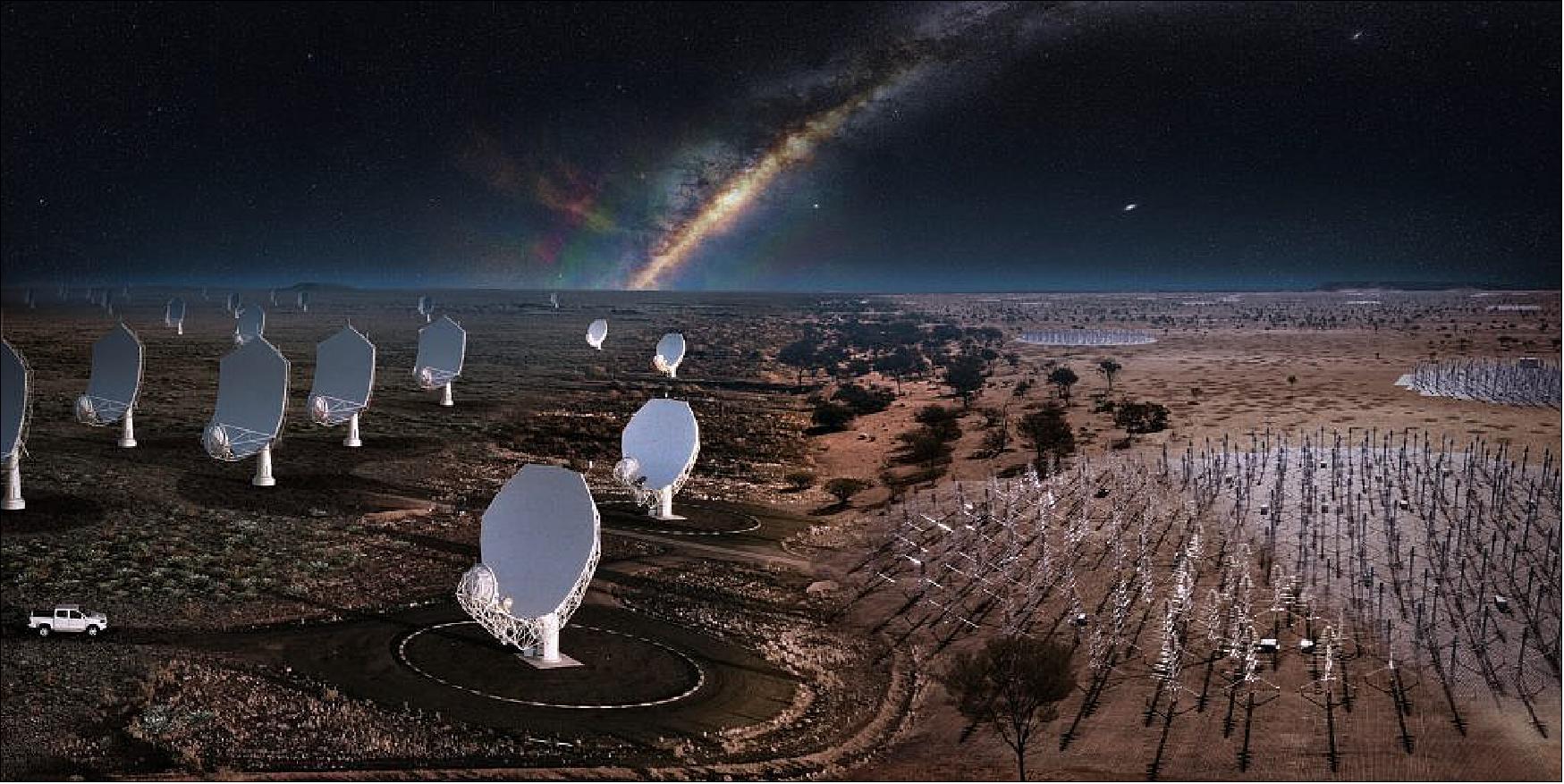

SKA telescopes function as interferometers, where multiple dishes or antennas act as a single unit to capture radio signals from celestial objects. The array aims to address major astronomical questions, such as galaxy formation, the nature of dark matter, and the existence of life on other planets.

To date, SKAO has secured €2.1 billion from its ten official members: Australia, Canada, China, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. This funding supports the first ten years of construction and operation (2021–2030), covering about 10% of the planned dishes and antennas. The initial phase includes 197 mid-frequency dishes in South Africa and 131,072 low-frequency antennas in Australia, both of which have already produced their first images.

New Collaborations

The second phase, initially slated for a 2020 start, aimed to include around 2,000 radio dishes in eight African nations: Botswana, Ghana, Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, and Zambia, along with South Africa. It also planned for one million antennas in Australia. The total collecting area would span around one square kilometre, giving the project its name.

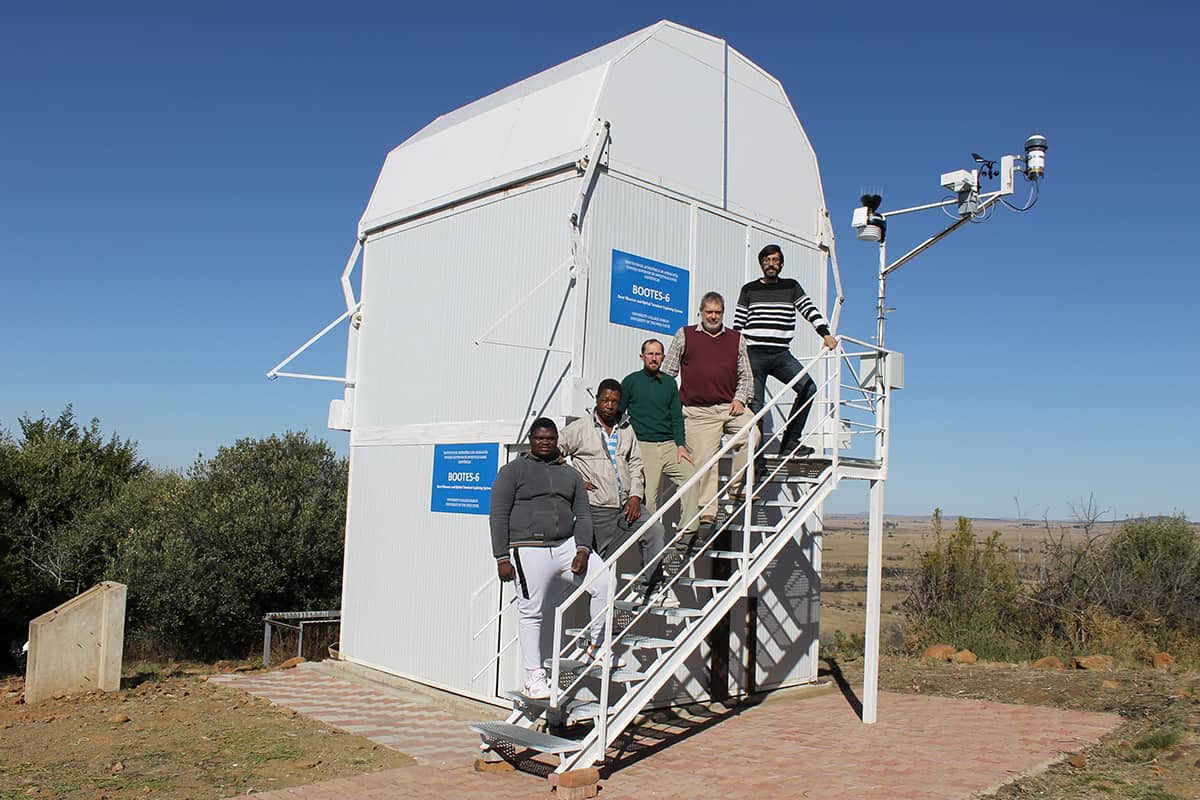

Despite the delay, Maruping affirmed that partnerships with African countries would continue. For example, Botswana is set to receive its first SKA dish next year through a collaboration with South Africa and Germany, funded separately from the original SKA plan.

Kgomotso Thelo, project manager at Botswana International University of Science and Technology (BIUST), highlighted the significance of Botswana's first SKA dish. "It’s a game-changer for science in Botswana," he said, adding that astronomers in the country would soon work on data generated from their own telescope.

Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy and the German Center for Astrophysics are contributing to the dish's hardware, valued at around €6 million. Botswana will cover infrastructure costs and provide local support, while South Africa supplies additional components.

International Support for African Astronomy

This new telescope in Botswana is part of a broader effort to boost astronomy infrastructure across Africa. The Max Planck Society, alongside the South African government and Italy’s Astronomical Observatory of Capodimonte, is also funding the addition of 14 dishes to South Africa’s MeerKAT telescope, which will eventually be integrated into the SKA.

The Botswana dish will similarly be incorporated into the SKA, marking the country’s first significant astronomical facility. Michael Bode, emeritus professor of astrophysics at Liverpool John Moores University, said this project will pave the way for more astronomical advancements in Botswana.

With just a few professional astronomers in Botswana, Thelo acknowledged the challenges ahead but expressed optimism: "It’s going to be a tough road, but having experienced partners makes it much easier for us."

With inputs from Nature Agency

Image Source: Multiple agencies

© Copyright 2024. All Rights Reserved Powered by Vygr Media.